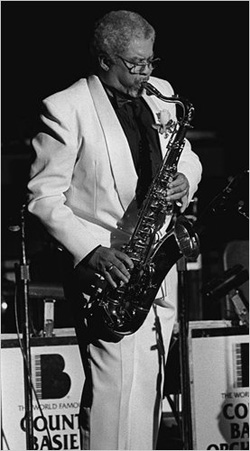

Frank Foster

Frank Foster, a saxophonist, composer and arranger who helped shape the sound of the Count Basie Orchestra during its popular heyday in the 1950s and ’60s and later led expressive large and small groups of his own, died on Tuesday at his home in Chesapeake, Va. He was 82.

Frank Foster, a saxophonist, composer and arranger who helped shape the sound of the Count Basie Orchestra during its popular heyday in the 1950s and ’60s and later led expressive large and small groups of his own, died on Tuesday at his home in Chesapeake, Va. He was 82.

The cause was complications of kidney failure, said his wife of 45 years, Cecilia. Mr. Foster had a varied and highly regarded career as a bandleader, notably with his Loud Minority Big Band, and he was sought after as an arranger for large ensembles. But it was the strength of his contribution to the so-called New Testament edition of the Basie band, from 1953 to 1964, that anchors his place in jazz history.

Mr. Foster wrote and arranged a number of songs for the band, none more celebrated than “Shiny Stockings,” a puckishly genteel theme set at a cruising medium tempo with a slow but powerful crescendo. Recorded by Basie on his classic 1955 album “April in Paris,” it subsequently became both a band signature and a jazz standard, often performed with lyrics (there were two sets, one by Ella Fitzgerald and one by Jon Hendricks).

Among Mr. Foster’s less famous entries in the Basie canon, some, like “Blues in Hoss’ Flat,” have enjoyed steady circulation in the repertories of high school and college jazz bands.

He was one of two musicians named Frank in the band’s saxophone section, the other being the tenor saxophonist and flutist Frank Wess. Their contrasting styles as soloists — Mr. Foster was the more robust, with a harder husk to his tone — became the basis of a popular set piece called “Two Franks,” written for the band by Neal Hefti.

He was one of two musicians named Frank in the band’s saxophone section, the other being the tenor saxophonist and flutist Frank Wess. Their contrasting styles as soloists — Mr. Foster was the more robust, with a harder husk to his tone — became the basis of a popular set piece called “Two Franks,” written for the band by Neal Hefti.

After leaving Basie, Mr. Foster worked for a while as a freelance arranger, supporting the likes of Frank Sinatra and Sarah Vaughan.

He returned to the Basie band in the mid-1980s, this time as its leader. (Count Basie died in 1984.) He held the post for nearly a decade and earned something like emeritus status: when the Count Basie Orchestra was enlisted for Tony Bennett’s 2008 album “A Swingin’ Christmas,” Mr. Foster was the arranger.

Frank Benjamin Foster III was born on Sept. 21, 1928, into Cincinnati’s African-American middle class — his father was a postal clerk, his mother a social worker — and began his musical studies first on piano, then clarinet. The alto saxophone came next, and within a year of picking it up he was playing in a neighborhood dance band.

Most of his early professional experience involved playing stock arrangements in big bands; during his senior year of high school he formed one himself, writing charts from scratch. He considered himself self-taught as an arranger, having studied only harmony in school.

Mr. Foster attended the historically black Wilberforce University in Ohio, after being rejected by Oberlin College and the Cincinnati Conservatory. He played in and arranged for Wilberforce’s dance band, the Collegians.

Mr. Foster attended the historically black Wilberforce University in Ohio, after being rejected by Oberlin College and the Cincinnati Conservatory. He played in and arranged for Wilberforce’s dance band, the Collegians.

As a budding tenor saxophonist he drew inspiration from Wardell Gray and Dexter Gordon, strong stylists who made the transition from swing to bebop. “I’m a hard bopper,” he told an interviewer with the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program in 1998. “Once a hard bopper, always a hard bopper.”

But Mr. Foster was hardly confined to bebop as a musical language. His tenure with the Count Basie Orchestra, which began after his tour of duty with the Army during the Korean War, proved as much.

So did his efforts after leaving Basie, when he played in smaller groups, including those led by his wife’s first cousin, the drummer Elvin Jones. At the time he was drawn to the adventurous music of John Coltrane, in whose quartet Mr. Jones had created an influential polyrhythmic pulse. An album called “Well Water,” recently released on the Piadrum label, captures Mr. Foster and Mr. Jones jointly leading the Loud Minority Big Band in 1977, with a determinedly modern mind-set. The album includes their take on “Simone,” Mr. Foster’s best-known post-Basie composition.

Even as he spent a good portion of the late 1960s and ’70s exploring harmonic and rhythmic abstraction, Mr. Foster never quite surrendered to it. And he was no purist about jazz-funk — “Manhattan Fever,” one of his best albums, released in 1968 on Blue Note, has several effervescent backbeat-driven tunes.

In 2001 Mr. Foster had a stroke that hindered his ability to play the saxophone. He was named a National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master the following year, and continued to write and arrange music, often as a commission for organizations like the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra. He also became active in the Jazz Foundation of America, a nonprofit organization that delivers aid to musicians in need.

In addition to his wife, Mr. Foster is survived by two children from their marriage, Frank Foster IV and Andrea Jardis Innis; two sons from his first marriage, Anthony and Donald; and six grandchildren.

Originally published in The New York Times