Author Archive

Thursday, October 1st, 2015

Before Milt Jackson, there were only two major vibraphonists: Lionel Hampton and Red Norvo. Jackson soon surpassed both of them in significance and, despite the rise of other players (including Bobby Hutcherson and Gary Burton), still won the popularity polls throughout the decades. Jackson (or “Bags” as he was long called) was at the top of his field for 50 years, playing bop, blues, and ballads with equal skill and sensitivity. Before Milt Jackson, there were only two major vibraphonists: Lionel Hampton and Red Norvo. Jackson soon surpassed both of them in significance and, despite the rise of other players (including Bobby Hutcherson and Gary Burton), still won the popularity polls throughout the decades. Jackson (or “Bags” as he was long called) was at the top of his field for 50 years, playing bop, blues, and ballads with equal skill and sensitivity.

Milt Jackson started on guitar when he was seven, and piano at 11; a few years later, he switched to vibes. He actually made his professional debut singing in a touring gospel quartet. After Dizzy Gillespie discovered him playing in Detroit, he offered him a job with his sextet and (shortly after) his innovative big band (1946). Jackson recorded with Gillespie, and was soon in great demand. During 1948-1949, he worked with Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Howard McGhee, and the Woody Herman Orchestra. After playing with Gillespie’s sextet (1950-1952), which at one point included John Coltrane, Jackson recorded with a quartet comprised of John Lewis, Percy Heath, and Kenny Clarke (1952), which soon became a regular group called the Modern Jazz Quartet. Although he recorded regularly as a leader (including dates in the 1950s with Miles Davis and/or Thelonious Monk, Coleman Hawkins, John Coltrane, and Ray Charles), Milt Jackson stayed with the MJQ through 1974, becoming an indispensable part of their sound. By the mid-’50s, Lewis became the musical director and some felt that Bags was restricted by the format, but it actually served him well, giving him some challenging settings. And he always had an opportunity to jam on some blues numbers, including his “Bags’ Groove.” However, in 1974, Jackson felt frustrated by the MJQ (particularly financially) and broke up the group. He recorded frequently for Pablo in many all-star settings in the 1970s, and after a seven-year vacation, the MJQ came back in 1981. In addition to the MJQ recordings, Milt Jackson cut records as a leader throughout his career for many labels including Savoy, Blue Note (1952), Prestige, Atlantic, United Artists, Impulse, Riverside, Limelight, Verve, CTI, Pablo, Music Masters, and Qwest. He died of liver cancer on October 9, 1999, at the age of 76.

By Scott Yanow

Posted in Artist of the Month | Comments Off on Milt Jackson

Tuesday, September 8th, 2015

VANCEBORO | Tom “The Jazzman” Mallison, a popular Public Radio East personality who hosted a weekly jazz show, was killed Sunday night in a two-vehicle, head-on crash on N.C. 43 in northwestern Craven County. VANCEBORO | Tom “The Jazzman” Mallison, a popular Public Radio East personality who hosted a weekly jazz show, was killed Sunday night in a two-vehicle, head-on crash on N.C. 43 in northwestern Craven County.

Friends say Mallison, who lived in Greenville, was headed home from PRE’s New Bern studios when the wreck occurred.

They believe Mallison was driving a Volvo. The other vehicle in the wreck has been identified as a Dodge pickup truck.

Additional details about the crash, including the name of the other driver involved and the circumstances of the wreck, were not available Monday. Ira Whitford, Craven County assistant emergency management director, said he had been told the crash happened at about 11:30 p.m. just north of Clark Road on N.C. 43.

A spokesperson at the N.C. Highway Patrol station in Williamston said Monday afternoon there was no report filed yet on the accident, and investigating Trooper S.M. Casner was not due back on duty until Monday night.

Vanceboro Fire Chief Stacey Lewis said the driver of the pickup had to be extricated from the vehicle. The driver was later flown to Vidant Medical Center in Greenville.

Mallison, who used the one-word name “TomtheJazzman” in promotions for his show, had finished hosting the five-hour “An Evening with TomtheJazzman” program Sunday night shortly before his death. The show ended at 11 p.m.

Charles Wethington, general manager for Public Radio East, said he was speechless Monday when he found out about Mallison’s death.

“He did his show last night and was going to Greenville where he lived,” Wethington said. “I’m still speechless really. It was such a tragic loss.”

Wethington said that when he came to work at the station 25 years ago Mallison was already working there.

“Tom has been on the air playing jazz with various stations for a very long time,” Wethington said. He was with Public Radio East since it began, about 30 years.”

Wethington said Mallison did a lot for jazz music.

“He had such a love for jazz,” he said. “Not only was he host of the jazz show on PRE, but Tom was known up and down the East Coast and throughout the United States. He attended a lot of jazz festivals and he knew so many jazz artists.”

Jill McGuire, assistant general manager at PRE, said Mallison and his show were popular with listeners here and elsewhere.

“He had such a passion for jazz,” she said. “He’s going to be missed by people in Eastern North Carolina and across the country.”

Wethington agreed.

By Eddie Fitzgerald and Sandy Wall

Originally published on www.newbernsj.com

Posted in Music News | Comments Off on Popular radio show host killed in Sunday crash

Sunday, August 2nd, 2015

Join us for a panel discussion of WNCU 90.7 FM’s past and present influential figures led by Lackisha Freeman, current general manager. Since its debut in August 1995, the station, licensed to North Carolina Central University, has consistently fulfilled its mission to provide quality culturally appropriate programming to public radio listeners.

Thursday, Aug. 6, 7 p.m.

Main Library, 300 N. Roxboro St.

This program is co-sponsored by WNCU 90.7 FM.

For more information call 919-560-0268 or visit durhamcountylibrary.org

Posted in Music News | Comments Off on WNCU From Its Debut to Present: Celebrating 20 Years of Art Through Sound

Saturday, August 1st, 2015

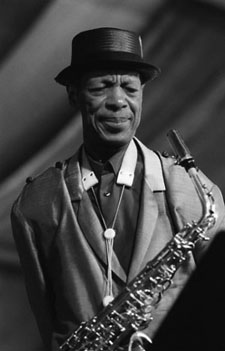

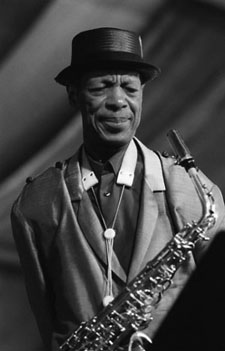

Ernie Andrews has managed to be both popular and underrated throughout his lengthy career. After his family moved to Los Angeles, he sang in a church choir, and while still attending high school had a few hits for the G&G label. Billy Eckstine and Al Hibbler were early influences and, after reaching maturity, Andrews was somewhat in the shadow of Joe Williams (who has a similar style). Andrews recorded for Aladdin, Columbia, and London in the late ’40s, spent six years singing with the Harry James Orchestra, and cut a couple of big band dates for GNP/Crescendo during 1958-1959. Despite his unchanging style, Andrews was mostly in obscurity during the 1960s and ’70s, just making a couple of albums for Dot during 1965-1966. A 1980 Discovery date found him in excellent form, and in the ’80s, he was rediscovered. Andrews recorded with the Capp/Pierce Juggernaut, Gene Harris’ Superband, Jay McShann, and with the Harper Brothers, in addition to making a few sets in the 1990s for Muse, and later High Note. He is also prominent in the documentary Blues for Central Avenue. Ernie Andrews has managed to be both popular and underrated throughout his lengthy career. After his family moved to Los Angeles, he sang in a church choir, and while still attending high school had a few hits for the G&G label. Billy Eckstine and Al Hibbler were early influences and, after reaching maturity, Andrews was somewhat in the shadow of Joe Williams (who has a similar style). Andrews recorded for Aladdin, Columbia, and London in the late ’40s, spent six years singing with the Harry James Orchestra, and cut a couple of big band dates for GNP/Crescendo during 1958-1959. Despite his unchanging style, Andrews was mostly in obscurity during the 1960s and ’70s, just making a couple of albums for Dot during 1965-1966. A 1980 Discovery date found him in excellent form, and in the ’80s, he was rediscovered. Andrews recorded with the Capp/Pierce Juggernaut, Gene Harris’ Superband, Jay McShann, and with the Harper Brothers, in addition to making a few sets in the 1990s for Muse, and later High Note. He is also prominent in the documentary Blues for Central Avenue.

Biography written by Scott Yanow and posted on allmusic.com.

Posted in Artist of the Month | Comments Off on Ernie Andrews

Thursday, July 30th, 2015

Come swing with North Carolina Central University’s alumni drummers and Thomas Taylor as they start the school year off with a Bang.

Jazz drummer Thomas Taylor and some of the Jazz percussion alumni will present a jazz concert and fundraiser in the B.N. Duke Auditorium on the campus of North Carolina Central University on Sunday, Aug. 2, at 6 p.m. Earlier in the afternoon, there will be music and percussion-centered workshops starting at 2 p.m., followed by a silent auction starting at 5 p.m. Auction winners will be announced before the final group performs in the evening concert.

All proceeds will go to the Jazz Studies scholarship fund. The concert is free and open to the public and Jazz Lovers! For more information, contact Thomas Taylor in the Department of Music at North Carolina Central University.

Posted in Music News | Comments Off on Give the Drummer Some… NCCU Jazz Percussion Faculty and Alumni Concert

Monday, July 6th, 2015

The Boston music scene has suffered another loss with the passing of the beautifully accomplished guitarist, author, and (at the Berklee College of Music) teacher, Garrison Fewell. He was 61. Last year we talked in his Somerville apartment. We were in his music room, where he sat in front of a wall of LPs. “Vinyl makes friends,” he joked to me. (Over the years we had spent afternoons together hunting for records in Manhattan.) His career was varied and in some ways unexpected. Its beginnings, though, were almost inevitable. When I asked about his musical upbringing, he waved at his record shelf, with its alphabetized recordings from Cannonball Adderley to Attila Zoller. He had listened to the hard bop recordings of his era: the Blue Notes, Riverside, and Prestige recordings. Still, starting at age 11, he was also playing the blues, imitating the sounds of John Hurt, Fred McDowell, and Gary Davis. The Boston music scene has suffered another loss with the passing of the beautifully accomplished guitarist, author, and (at the Berklee College of Music) teacher, Garrison Fewell. He was 61. Last year we talked in his Somerville apartment. We were in his music room, where he sat in front of a wall of LPs. “Vinyl makes friends,” he joked to me. (Over the years we had spent afternoons together hunting for records in Manhattan.) His career was varied and in some ways unexpected. Its beginnings, though, were almost inevitable. When I asked about his musical upbringing, he waved at his record shelf, with its alphabetized recordings from Cannonball Adderley to Attila Zoller. He had listened to the hard bop recordings of his era: the Blue Notes, Riverside, and Prestige recordings. Still, starting at age 11, he was also playing the blues, imitating the sounds of John Hurt, Fred McDowell, and Gary Davis.

He was a committed pacifist in the middle of the Vietnam war. At the age of 18 Fewell left the country. He started off living at a kibbutz in Israel and then travelled with his guitar and a friend who played the harmonica to Afghanistan. When he learned he had been drafted, he decided to stay overseas. In the Bamiyan Valley, standing next to the ear of a giant Buddha, he had his first encounter with Buddhism, which he would practice for the rest of his life. It was, as he describes it, a mystical experience. Then he returned to go to the Berklee College of Music, where, having focused on what his peers called “chicken-pickin’ music,” and feeling that the music of Coltrane and Charlie Parker were beyond him, he studied bossa nova. He would graduate in 1977. In 1992 he led his first recording, A Blue Deeper Than Blue. He was already well known in Europe. Guitarist Larry Coryell predicted that this recording would make him an idol here as well.

He spent the next decade teaching and playing his particularly gentle, often humorous compositions in prestigious clubs, including New York’s Birdland, where he recorded Birdland Sessions. He found the time to write two respected guitar manuals: Jazz Improvisation for Guitar: A Melodic Approach and Jazz Improvisation for Guitar: A Harmonic Approach. During this period he was becoming increasingly disillusioned with some of the competitive aspects of the jazz scene, which he referred to as “the world of hungry spirits.” (The “hungry spirits” were “the musicians who were always trying to get another gig, another review.”) He had, he said, changed inside, and his music also had to change. He began to work on freer improvisations.

The breakthrough, or breakup as some of his unhappy bebopping fans thought, came in 2003 at Cambridge’s Regattabar, where he played so freely it even disturbed his bass player. He was on his way to experimenting with group improvisation. Later he would work with Danish saxophonist John Tchicai, who had appeared on John Coltrane’s Ascension. Last year he published Outside Music, Inside Voices (Arts Fuse review), his compelling book of interviews with free jazz players, who explained their commitment to their approach, often in beautifully evocative language. His fans will remember his performances in recent years, sometimes in his house concerts or in small venues around Boston. They were challenging, and yet often charming. Sometimes they just took off.

He described to me the best parts of his recent performances: “At a certain moment, even in the midst of chaos, a ‘sound unity’ will occur—you can hear it happen—where individual and collective exploration converge and the music becomes connected to a greater energy. The vibrations in the room become more intense, the overtones more pronounced. It’s a physical as well as emotional energy that unifies body and mind. When it’s over, everyone in the room knows something happened. But what? The question remains to be answered by the performers and audience, but from a player’s point of view, I can say that it never happens the same way or in the same place twice.” He made sure it didn’t. He never settled for the second rate or avoided a challenge. His illness was his latest obstacle: through it all he wrote his book, played as often as he could, and continued to chant every day. When I visited him recently, he gleefully showed off the contents of a guitar case full of odds and ends, hunks of metal, a violin bow, and whatever, with which he modified the sound of his guitar. He had decided to live in the moment, and it proved rewarding.

The music, and his own playfulness, sustained him. When he first became ill, he stopped playing for three months. Then he was invited to perform an improvised concert at the Outpost. Fewell told me about the experience:

I was really weak coming in there. We improvised. There was no rehearsal. We hadn’t talked about anything about what we were going to do. We played and at the end of it, something so incredible happened. It was like . . . what did Steve Lacy say? Something about lifting the band off the bandstand. We were in another dimension, and so was the audience. The overtones and the sound filled the room and it was intense and it was just blasting at the end and then it was just Boom! Just done. That changed my life. From that moment I knew, there’s something that’s beyond. No matter how far you’ve thought you’ve gone, or what strengths you may or may not have, there’s something more to this music. That began my process of healing.

In 1995 Fewell made a recording, Are You Afraid of the Dark? The title seems prophetic. Diagnosed with cancer, he faced the darkness and then turned away. In an interview with me, he spoke about waking up from his first operation and immediately realizing that he had a decision to make. Before the surgery, he felt that he had a number of problems to deal with: “But when you are facing life and death, because they haven’t found a cure yet to make my illness a chronic disease like diabetes or HIV, you only have two choices. It becomes very simple. You go down one road, there’s darkness and death down there. Or you go down another road, which is positive and light and joy and really being in the moment and appreciating every single moment that you have. I have to make that choice . . . it’s just between those two.”

An inspiring man as well as a brilliant musician, Fewell had the courage to turn away from the darkness and to embrace the light. We shall not forget him.

By Michael Ullman

Originally published on artsfuse.org

Posted in Music News | Comments Off on Guitarist Garrison Fewell — The Master of Searching for Something More

Wednesday, July 1st, 2015

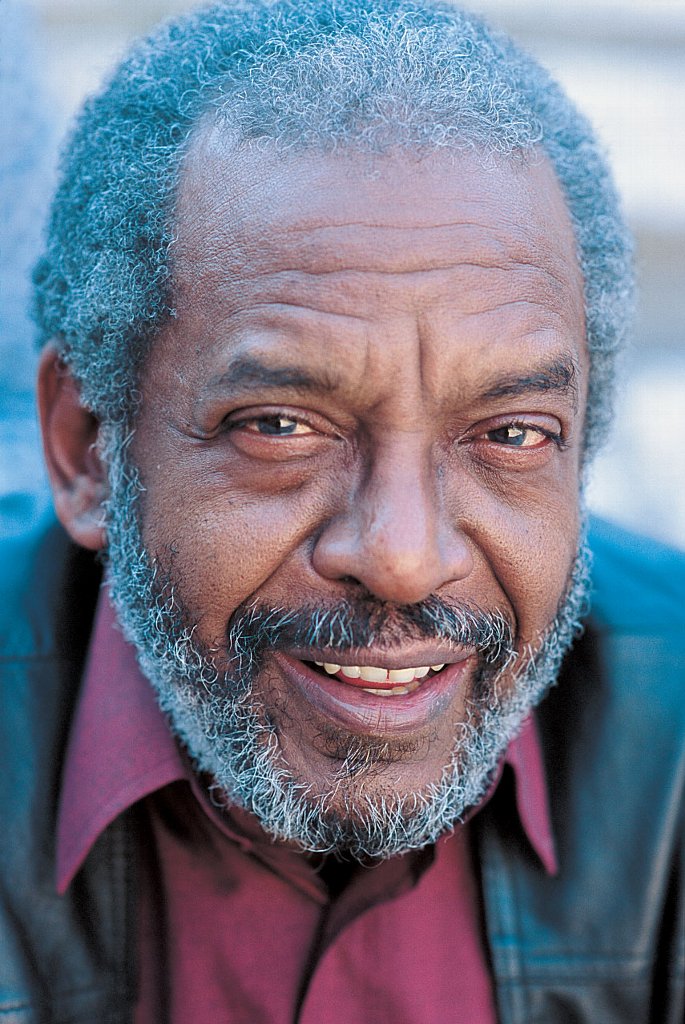

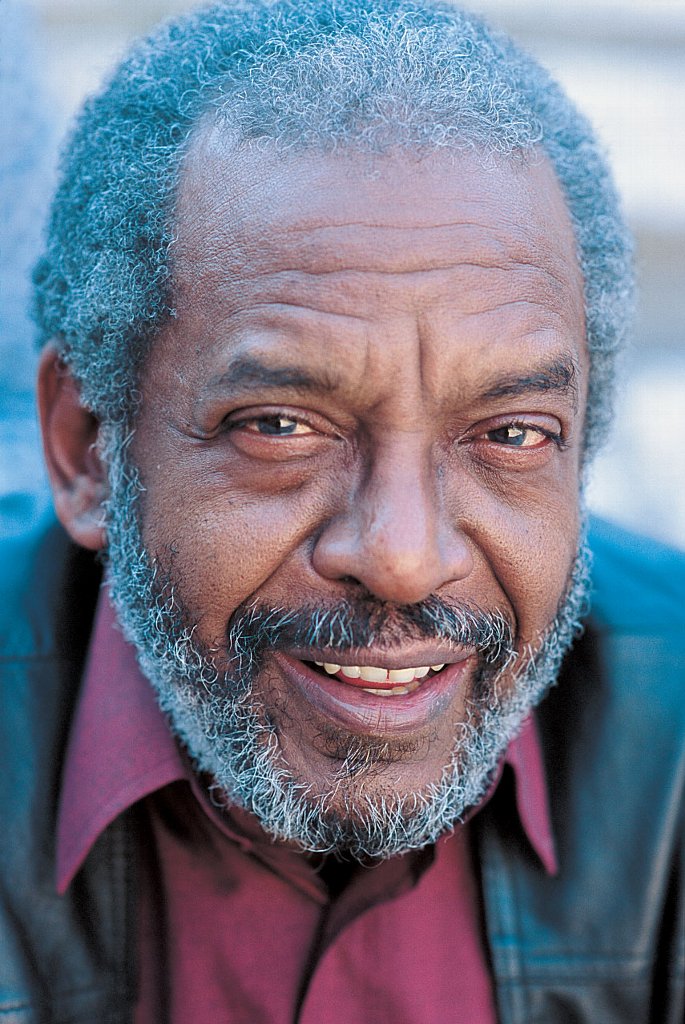

Early on in his career, alto saxophonist Ornette Coleman, recorded an album entitled, The Shape of Jazz To Come. It might have seemed like an expression of youthful arrogance – Coleman was 29 at the time – but actually, the title was prophetic. Coleman is the creator of a concept of music called “harmolodic,” a musical form which is equally applicable as a life philosophy. The richness of harmolodics derives from the unique interaction between the players. Breaking out of the prison bars of rigid meters and conventional harmonic or structural expectations, harmolodic musicians improvise equally together in what Coleman calls compositional improvisation, while always keeping deeply in tune with the flow, direction and needs of their fellow players. In this process, harmony becomes melody becomes harmony. Ornette describes it as “Removing the caste system from sound.” On a broader level, harmolodics equates with the freedom to be as you please, as long as you listen to others and work with them to develop your own individual harmony. Early on in his career, alto saxophonist Ornette Coleman, recorded an album entitled, The Shape of Jazz To Come. It might have seemed like an expression of youthful arrogance – Coleman was 29 at the time – but actually, the title was prophetic. Coleman is the creator of a concept of music called “harmolodic,” a musical form which is equally applicable as a life philosophy. The richness of harmolodics derives from the unique interaction between the players. Breaking out of the prison bars of rigid meters and conventional harmonic or structural expectations, harmolodic musicians improvise equally together in what Coleman calls compositional improvisation, while always keeping deeply in tune with the flow, direction and needs of their fellow players. In this process, harmony becomes melody becomes harmony. Ornette describes it as “Removing the caste system from sound.” On a broader level, harmolodics equates with the freedom to be as you please, as long as you listen to others and work with them to develop your own individual harmony.

For his essential vision and innovation, Coleman has been rewarded by many accolades, including the MacArthur “Genius” Award, and an induction into the American Academy of Arts and Letter. an honorary doctorate degree from the University of Pennsylvania, the American Music Center Letter of Distinction, and the New York State Governor Arts Award.

But the path to his present universal acclaim has not always been smooth.

Born in a largely segregated Fort Worth, Texas on March 9, 1930, Coleman’s father died when he was seven. His seamstress mother worked hard to buy Coleman his first saxophone when he was 14 years old. Teaching himself sight-reading from a how-to piano book, Coleman absorbed the instrument and began playing with local rhythm and blues bands.

In his search for a sound that expressed reality as he perceived it,

Coleman knew he was not alone. The competitive cutting sessions that denoted ‘bebop’ were all about self-expression in the highest form. “I could play and sound like Charlie Parker note-for-note, but I was only playing it from method. So I tried to figure out where to go from there,” Coleman said.

Los Angeles proved to be the laboratory for what came to be called free jazz. There began to gather around Ornette a core of players who would figure largely in his life: a lanky teenage trumpeter, Don Cherry and a cherubic double bass player with a pensive, muscular style named Charlie Haden, drummers Ed Blackwell and Billy Higgins also joined the intense exploratory rehearsals in which Coleman was honing his vocabulary on a plastic sax, despite the lack of live gigs. Los Angeles proved to be the laboratory for what came to be called free jazz. There began to gather around Ornette a core of players who would figure largely in his life: a lanky teenage trumpeter, Don Cherry and a cherubic double bass player with a pensive, muscular style named Charlie Haden, drummers Ed Blackwell and Billy Higgins also joined the intense exploratory rehearsals in which Coleman was honing his vocabulary on a plastic sax, despite the lack of live gigs.

But simply by persisting, Coleman’s creativity attracted champions. Bebop bassist, Red Mitchell (an old associate of Cherry’s) brought the saxophone player’s to Contemporary Records’ Lester Koenig, originally intending to sell him some of his compositions. After realizing the difficulty musicians were having in playing the music Koenig asked Coleman if he could play the tunes himself. The meeting led to the Coleman’s debut 1958 album, Something Else.

The energy and electricity that had been building around Ornette and his players exploded during a now legendary season that Coleman played at the Five Spot jazz club in New York in November, 1959. Intrigued by rumors of the unorthodox young Texan’s approach, buzz preceded the shows and as the initial two weeks extended to a six-week run, the revolutionary Coleman quartet became the must-see event of the season.

And yet, as writer and long-time Coleman associate, Robert Palmer, observes in his notes to the Beauty Is A Rare Thing box set of the Atlantic years (Rhino/Atlantic), “The present day listener will most likely hear these pieces as well conceived and superbly realized works on their own terms and will again wonder what all the controversy could have been about.”

Coleman soon began to study of the trumpet and violin expanding the scope of his always prolific composition to include string quartets, woodwind quintets and symphonic works. Coleman used a Guggenheim Foundation grant to write a symphony, Skies of America.

Coleman went on a journey to Morocco in 1973, to work with the Master Musicians of Jajouka in their mountain villages. Following he also visited villages in Nigeria. Soon upon his return Coleman created with a new sound that was a full frontal harmolodic attack, a double whammy of drums and electric bass, dubbed Prime Time.

Coleman’s 1986 collaboration with jazz-rock guitarist Pat Metheny, Song X led to a tour and a new audience. Ornette moved into the broader public consciousness in the late 80s by performing and recording with the Grateful Dead and their hippy virtuoso guitarist, Jerry Garcia. The affection and respect which Coleman and the late Garcia had for one another was captured in the sessions for 1988’s Virgin Beauty (CBS/Portrait). Coleman’s 1986 collaboration with jazz-rock guitarist Pat Metheny, Song X led to a tour and a new audience. Ornette moved into the broader public consciousness in the late 80s by performing and recording with the Grateful Dead and their hippy virtuoso guitarist, Jerry Garcia. The affection and respect which Coleman and the late Garcia had for one another was captured in the sessions for 1988’s Virgin Beauty (CBS/Portrait).

The new autonomy heralded a season in which Coleman began to reap consistent accolades for his continued adventures in music. He formed the Harmolodic Label and began an association with Polygram France. Over the course of the decade Harmolodic released a number of works beginning with Tone Dialing, on which a Bach prelude is rendered harmolodically.

One of the ultimate American accolades, the MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant, was awarded to Coleman in 1994. In general, rather than simple concerts, Coleman’s performances had by now become big multimedia events that both reflected and impacted on the host town’s community, lasting for several nights at a significant location.

Lincoln Center provided the backdrop for Civilization 1997. A four-night event at Avery Fisher Hall. It began with two nights of Kurt Masur conducting the New York Philharmonic together with Prime Time. Perhaps the most eagerly awaited aspect of all four nights was the first New York appearance in two decades of the Original Quartet, performing all new material. Hearing the familiar, still stimulating blend of Coleman, Haden and Higgins was an emotional experience for many listeners, who found in the depth of the players’ empathy a yardstick of their own lives and the fulfillment of dreams they had when they first heard the Quartet shatter conceptions of music.

A metaphysician, philosopher and eternal student, Coleman continues to confound categorization. His Harmolodic world continues to expand along with the concepts of an artist beyond boundaries. “Most people think of me only as a saxophonist and as a jazz artist,” he once stated, “but I want to be considered as a composer who could cross over all the borders.”

Bio originally published on allaboutjazz.com.

Posted in Artist of the Month | 6 Comments »

Tuesday, June 30th, 2015

Beginning July 6th, Jazz Overnight, heard daily on WNCU, will add two new charismatic, deeply knowledgeable veteran Jazz hosts, Lee Thomas and Greg Bridges. Both long time jazz experts from award winning station KCSM in California, Lee and Greg will program and announce new sets for our overnight jazz listeners at WNCU. WNCU welcomes Lee and Greg… new voices dedicated to bringing you mainstream jazz.

Greg Bridges

Born and raised in Oakland, California, Greg Bridges has been in radio for nearly 30 years. In addition to his live shifts on KCSM, he hosts Transitions and Traditions, a spoken-word and Jazz show on KPFA Radio in Berkeley. A seasoned Jazz writer, emcee and presenter, he also showcases music and spoken word artists at various venues in Oakland. An alumnus of San Jose State University, Greg began his professional radio career at KJAZ Radio in Alameda, California where he came into his own as an on-air announcer, interviewer and host of a variety of shows. The proud dad of two children, Simone and Miles, Greg was musically inspired by his drum playing father, the late Oliver Johnson. He moved to Europe in 1970 and spent 16 years drumming for Steve Lacy, Roswell Rudd, Roscoe Mitchell, Jean Luc Ponty, Archie Shepp and others. “Being in broadcasting has brought me many bright moments,” he notes, “Hanging out in a dressing room with Harry ‘Sweets’ Edison, sharing jokes and conversation with Miles Davis, receiving a gift in the mail for my newborn daughter from Betty Carter. There have been and continue to be many bright moments.”

Lee Thomas

Jazz host and composer Lee Thomas started his radio career with the legendary San Francisco station KJAZ and then at KNBR as well as NBC News in Burbank, CA. His Jazz epiphany came when his father brought home an album from a car show he attended. “Chrysler put out this anthology record that had Lambert, Hendricks and Ross on it along with Sir Charles Thompson, Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Dave Brubeck and others. The more I listened to it, the more I liked it. Soon a friend and I started going up to Telegraph Ave. in Berkeley and searching for Jazz albums in the used record stores.” Lee picked up a trumpet in his late teens and aspired to someday be a professional musician. He studied with John Coppola, Warren Gale Jr., Eddie Henderson, Woody Shaw and Joe Henderson. He has penned compositions for three albums under his name: Sea of Dreams, Passions of the Heart, and Convergence. Each recording showcases imaginative themes with superb solos by musicians like Billy Childs, Tony Dumas, Akira Tana, Pete Escovedo and others.

Posted in Music News | Comments Off on New Hosts for Jazz Overnight Beginning July 6

Monday, June 22nd, 2015

Gunther Schuller, a composer, conductor, author and teacher who coined the term Third Stream to describe music that drew on the forms and resources of both classical and jazz, and who was its most important composer, died on Sunday in Boston. He was 89. Gunther Schuller, a composer, conductor, author and teacher who coined the term Third Stream to describe music that drew on the forms and resources of both classical and jazz, and who was its most important composer, died on Sunday in Boston. He was 89.

The cause was complications of leukemia, said his personal assistant, Jennique Horrigan.

Mr. Schuller, who won the Pulitzer Prize for his orchestral work “Of Reminiscences and Reflections” in 1994, was partial to the 12-tone methods of the Second Viennese School, but he was not inextricably bound to them. Always fascinated by jazz, he wrote arrangements as well as compositions for several jazz artists, most notably the Modern Jazz Quartet. Several of his scores — among them the Concertino (1958) for jazz quartet and orchestra, the “Seven Studies on Themes of Paul Klee” (1959) and an opera, “The Visitation” (1966) — used aspects of his Third Stream aesthetic, though usually with contemporary classical influences dominating.

Much of Mr. Schuller’s best music is scored for unusual instrumental combinations. In the Symphony for Brass and Percussion (1950), one of his most widely performed early works, he sent the strings and woodwinds to the sidelines. In “Spectra,” a study in orchestral color composed for the New York Philharmonic in 1960, he split the orchestra into seven distinct groups, deployed separately on the stage so that each could be heard independently or in combination with the others. He also composed “Five Pieces for Five Horns” (1952) and quartets for four double basses (1947) and four cellos (1958). His more than 20 concertos include showpieces for the double bass (1968), the contrabassoon (1978) and the alto saxophone (1983), as well as a Grand Concerto for Percussion and Keyboards (2005), for eight percussionists, a harpist and two keyboardists.

Some of his works were thorny and brash. But they could also be poetic and evocative. “Of Reminiscences and Reflections,” a rich, emotionally direct orchestral score, was composed as an elegy for Mr. Schuller’s wife, Marjorie, who died in November 1992. In his “Impromptus and Cadenzas” (1990), a chamber work, harmonic spikiness was offset by currents of lyricism and unpredictable shifts of mood and tone color.

As a composer, Mr. Schuller was self-taught. Although his career took him from the horn section of the Cincinnati Symphony and the pit of the Metropolitan Opera to a handful of influential positions — among them the presidency of the New England Conservatory and the artistic directorship of the Berkshire Music Center at Tanglewood — he once described himself as “a high school dropout without a single earned degree.”

That he made this comment in a speech before the American Society of University Composers, in March 1980, was typical of Mr. Schuller. In addition to being fiercely proud of his self-taught status, he had an iconoclastic streak, and had a busy sideline delivering jeremiads in which he railed against either his listeners’ approach to music making or the musical world in general.

He told the university composers, for example, that it was time to abandon intellectual complexity for its own sake, and to write music that audiences could embrace — this despite his own devotion to the 12-tone method, which many listeners regarded as the root of the audience’s estrangement.

Only a few months earlier, in June 1979, Mr. Schuller had caused a stir by greeting the students who had come to Tanglewood to study at the Berkshire Music Center with an address in which he excoriated orchestras, orchestral musicians, conductors and unions for creating a situation in which, as he put it, “joy has gone out of the faces of many of our musicians,” replaced by “apathy, cynicism, hatred of new music” and other ills. Some of his arguments found their way into a compilation of his essays, “Musings: The Musical Worlds of Gunther Schuller” (1986), and his 1997 book, “The Compleat Conductor.”

But if Mr. Schuller learned composition on his own, he approached it with a solid grounding in musical basics. His paternal grandfather had been a conductor and teacher in Germany, and his father, Arthur Schuller, had played the violin in Germany under Wilhelm Furtwängler. Arthur Schuller joined the New York Philharmonic as a violinist and violist in 1923 and remained with the orchestra until 1965, and he encouraged his son to take up the flute and the French horn on the grounds that woodwind and brass players were in shorter supply than string players.

“I was fortunate to have been born into a musical home,” Mr. Schuller told The New York Times in 1977. “My father played with the New York Philharmonic for 42 years, and he had a lot of scores. When I was 11 or 12, I began buying my own scores, and at 13 I became a rabid record collector. Then, of course, there was playing. All of those things were my teachers, and they all complemented each other.”

Gunther Alexander Schuller was born in Queens on Nov. 22, 1925, to Arthur Schuller and the former Elsie Bernartz. After attending a private school in Gebesee, Germany, from 1932 to 1936, he returned to New York and enrolled at the St. Thomas Church Choir School, where he studied music with T. Tertius Noble and sang as a boy soprano. He also began to study the flute and the French horn, and was engaged by the Philharmonic as a substitute hornist when he was 15. He attended Jamaica High School in Queens; during his high school years, he also studied music theory and counterpoint at the Manhattan School of Music.

In 1943, Mr. Schuller dropped his studies to take his first professional job, touring as a French hornist with the American Ballet Theater. That same year he became the principal hornist of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, a position he held until 1945, when he moved back to New York and became the principal hornist at the Metropolitan Opera. He was already composing as well, and before he left Cincinnati he was the soloist in the premiere of his own First Horn Concerto (1945).

It was also in Cincinnati that Mr. Schuller became interested in jazz, primarily through the music of Duke Ellington, which he transcribed from recordings and arranged for the Cincinnati Pops. As a player he began living a double life in New York, performing at the Metropolitan Opera and in chamber music concerts, and in ensembles led by, among others, Miles Davis.

He also began to temper his concert music with jazz elements, and he wrote a series of works to perform with the jazz pianist John Lewis, with both the Modern Jazz Quartet and a larger ensemble, the Modern Jazz Society. Typically, in these collaborations, Lewis would lead a jazz ensemble augmented by strings or woodwinds, which Mr. Schuller conducted.

In 1957, Mr. Schuller began describing these classical-jazz hybrids as Third Stream music. An important early showcase for the concept was a concert in May 1960 at the Circle in the Square theater, in which the Contemporary String Quartet and a starry cast of jazz musicians — among them the pianist Bill Evans and his trio, the guitarist Barry Galbraith, the multi-reed player Eric Dolphy and the alto saxophonist Ornette Coleman (who died on Thursday) — played a sampling of Mr. Schuller’s Third Stream works. He continued to champion the notion of Third Stream music throughout his career, sometimes expanding its definition.

“The Third Stream movement,” he once said, “inspires composers, improvisers and players to work together toward the goal of a marriage of musics, whether ethnic or otherwise, that have been kept apart by the tastemakers — fusing them in a profound way. And I think it’s appropriate that this has happened in this country, because America is the original cultural melting pot.”

For about 15 years, Mr. Schuller balanced his performing and composing careers by composing all night after playing opera performances. But by 1959 his schedule had become too arduous, and he decided to give up performing to devote himself more fully to composition.

The vacuum created by giving up his playing job was quickly filled with other noncompositional activities. In 1962 he published his first book, “Horn Technique,” which quickly became a standard reference work and was revised in 1992. In 1963 he began directing “20th Century Innovations,” a new-music series that ran for several seasons at Carnegie (now Weill) Recital Hall. That summer he was appointed acting head of the composition faculty at Tanglewood, and he took over the department fully in 1965. He soon became a powerful force at Tanglewood, directing the Berkshire Music Center from 1970 to 1984.

After he resigned from Tanglewood, he started a summer festival in Sandpoint, Idaho. He was also the music director of the Spokane Symphony for the 1984-85 season, and he maintained relationships with several other ensembles, including the Pro Arte Chamber Orchestra in Boston, of which he was principal guest conductor, and the Smithsonian Jazz Masterworks Orchestra in Washington, of which he was co-director with David Baker.

Mr. Schuller’s teaching career began in 1950, when he joined the faculty of the Manhattan School of Music. He taught composition at Yale from 1964 to 1967, when he was appointed president of the New England Conservatory. During his decade in that position, he introduced jazz and Third Stream music as focuses of conservatory training.

His own research into jazz proved fruitful as well. His “Early Jazz: Its Roots and Musical Development” (1968) and “The Swing Era: The Development of Jazz, 1930-1945” (1989) are highly regarded histories, and his recording of Scott Joplin’s “Red Back Book,” with the New England Conservatory Ragtime Ensemble, won a Grammy in 1974 and helped start the ragtime revival of the mid-1970s.

In 1975 Mr. Schuller established his own publishing companies, Gun-Mar Music and Margun Music, and in 1981 he started a record label, GM Recordings. With these companies, he produced printed editions of everything from early music to jazz transcriptions and contemporary works, as well as a large catalog of recordings by classical and jazz players, among them the Kronos Quartet, the pianists Russell Sherman, Frederick Moyer and Ran Blake, the saxophonist Joe Lovano and the guitarist Jim Hall.

Mr. Schuller, who lived in Newton Centre, Mass., is survived by his sons, Edwin and George, both professional musicians. In addition to the Pulitzer Prize, Mr. Schuller was awarded a MacArthur Foundation grant in 1991; the William Schuman Award, from Columbia University, in 1989; a Jazz Masters Fellowship (for advocacy) from the National Endowment for the Arts in 2008; and a lifetime achievement medal from the MacDowell Colony this year. “As a composer and teacher,” the composer Augusta Read Thomas, the chairwoman of the selection committee for the MacDowell award, said at the time, “he has inspired generations of students, setting an example of discovery and experimentation.”

In 2011 he published an autobiography, “Gunther Schuller: A Life in Pursuit of Music and Beauty.” That same year, he was the subject of a tribute concert at Weill Recital Hall, featuring two works by Mr. Schuller and two by the young composer Mohammed Fairouz.

In a laudatory review of that concert for The Times, Zachary Woolfe wrote of Mr. Schuller, “He has, as Mr. Fairouz said in an onstage discussion, big ears.”

Originally published at www.nytimes.com

Posted in Music News | Comments Off on Gunther Schuller Dies at 89; Composer Synthesized Classical and Jazz

Monday, June 22nd, 2015

Wendell Holmes, vocalist, guitarist, pianist and songwriter of the critically acclaimed soul/blues band The Holmes Brothers, died on Friday, June 19 at his home in Rosedale, Maryland of complications due to pulmonary hypertension. Earlier this week, Wendell addressed his fans and friends in an open letter as he moved into hospice care. He was 71. Wendell Holmes, vocalist, guitarist, pianist and songwriter of the critically acclaimed soul/blues band The Holmes Brothers, died on Friday, June 19 at his home in Rosedale, Maryland of complications due to pulmonary hypertension. Earlier this week, Wendell addressed his fans and friends in an open letter as he moved into hospice care. He was 71.

Wendell retired from touring earlier this year when he was first diagnosed. Holmes Brothers drummer Willie “Popsy” Dixon died on January 9, 2015 of complications from cancer. Brother and bassist Sherman Holmes continues to carry on The Holmes Brothers legacy with The Sherman Holmes Project featuring Brooks Long and Eric Kennedy.

Wendell, the man Entertainment Weekly has called “a timeless original,” was born in Christchurch, Virginia on December 19, 1943. He and his older brother Sherman were raised by their schoolteacher parents, who nurtured the boys’ early interest in music. As youngsters they listened to traditional Baptist hymns, anthems and spirituals as well as blues music by Jimmy Reed, Junior Parker and B.B. King. According to Wendell, “It was a small town, and my brother and I were about the only ones who could play anything. So we played around in all the area churches on Sundays.” The night before, though, they would play blues, soul, country and rock at their cousin’s local club, Herman Wate’s Juke Joint. “When he couldn’t get any good groups to come from Norfolk or Richmond, he’d call us in,” Wendell recalls. “That’s how we honed our sound. We used to say we’d rock ‘em on Saturday and save ‘emon Sunday.”

Once Wendell finished high school he joined Sherman, who had already begun playing professionally in New York. The two brothers played in a few bands before forming The Sevilles in 1963. The group lasted only three years, but they often backed up touring artists like The Impressions, John Lee Hooker and Jerry Butler, gaining a wealth of experience. Sherman and Wendell met drummer Popsy Dixon, a fellow Virginian, at a New York gig in 1967. Dixon sat in with the brothers and sang two songs. “After that second song,” recalls Wendell, “Popsy was a brother.” They continued to play in a variety of Top 40 bar bands until 1979, when the three officially joined forces and formed The Holmes Brothers band.

The band toured the world, releasing 12 albums starting with 1990’s In The Spirit on Rounder. Their most recent release is 2014’s Brotherhood on Alligator. The New York Times calls The Holmes Brothers “deeply soulful, uplifting and timeless.”

In September 2014, The Holmes Brothers were honored with a National Endowment For The Arts National Heritage Fellowship, the highest honor the United States bestows upon its folk and traditional artists. They won two Blues Music Awards including Blues Band Of The Year in 2005. The Holmes Brothers are featured on the cover of the current issue of Living Blues magazine.

Wendell is survived by his wife, Barbara, daughters Felicia and Mia, brothers Sherman and Milton, and three grandsons.

Memorial service arrangements have not yet been announced.

Originally published on www.alligator.com

Posted in Music News | Comments Off on Wendell Holmes, 1943 – 2015

|

Before Milt Jackson, there were only two major vibraphonists: Lionel Hampton and Red Norvo. Jackson soon surpassed both of them in significance and, despite the rise of other players (including Bobby Hutcherson and Gary Burton), still won the popularity polls throughout the decades. Jackson (or “Bags” as he was long called) was at the top of his field for 50 years, playing bop, blues, and ballads with equal skill and sensitivity.

Before Milt Jackson, there were only two major vibraphonists: Lionel Hampton and Red Norvo. Jackson soon surpassed both of them in significance and, despite the rise of other players (including Bobby Hutcherson and Gary Burton), still won the popularity polls throughout the decades. Jackson (or “Bags” as he was long called) was at the top of his field for 50 years, playing bop, blues, and ballads with equal skill and sensitivity.

VANCEBORO | Tom “The Jazzman” Mallison, a popular Public Radio East personality who hosted a weekly jazz show, was killed Sunday night in a two-vehicle, head-on crash on N.C. 43 in northwestern Craven County.

VANCEBORO | Tom “The Jazzman” Mallison, a popular Public Radio East personality who hosted a weekly jazz show, was killed Sunday night in a two-vehicle, head-on crash on N.C. 43 in northwestern Craven County. Ernie Andrews has managed to be both popular and underrated throughout his lengthy career. After his family moved to Los Angeles, he sang in a church choir, and while still attending high school had a few hits for the G&G label. Billy Eckstine and Al Hibbler were early influences and, after reaching maturity, Andrews was somewhat in the shadow of Joe Williams (who has a similar style). Andrews recorded for Aladdin, Columbia, and London in the late ’40s, spent six years singing with the Harry James Orchestra, and cut a couple of big band dates for GNP/Crescendo during 1958-1959. Despite his unchanging style, Andrews was mostly in obscurity during the 1960s and ’70s, just making a couple of albums for Dot during 1965-1966. A 1980 Discovery date found him in excellent form, and in the ’80s, he was rediscovered. Andrews recorded with the Capp/Pierce Juggernaut, Gene Harris’ Superband, Jay McShann, and with the Harper Brothers, in addition to making a few sets in the 1990s for Muse, and later High Note. He is also prominent in the documentary Blues for Central Avenue.

Ernie Andrews has managed to be both popular and underrated throughout his lengthy career. After his family moved to Los Angeles, he sang in a church choir, and while still attending high school had a few hits for the G&G label. Billy Eckstine and Al Hibbler were early influences and, after reaching maturity, Andrews was somewhat in the shadow of Joe Williams (who has a similar style). Andrews recorded for Aladdin, Columbia, and London in the late ’40s, spent six years singing with the Harry James Orchestra, and cut a couple of big band dates for GNP/Crescendo during 1958-1959. Despite his unchanging style, Andrews was mostly in obscurity during the 1960s and ’70s, just making a couple of albums for Dot during 1965-1966. A 1980 Discovery date found him in excellent form, and in the ’80s, he was rediscovered. Andrews recorded with the Capp/Pierce Juggernaut, Gene Harris’ Superband, Jay McShann, and with the Harper Brothers, in addition to making a few sets in the 1990s for Muse, and later High Note. He is also prominent in the documentary Blues for Central Avenue. The Boston music scene has suffered another loss with the passing of the beautifully accomplished guitarist, author, and (at the Berklee College of Music) teacher, Garrison Fewell. He was 61. Last year we talked in his Somerville apartment. We were in his music room, where he sat in front of a wall of LPs. “Vinyl makes friends,” he joked to me. (Over the years we had spent afternoons together hunting for records in Manhattan.) His career was varied and in some ways unexpected. Its beginnings, though, were almost inevitable. When I asked about his musical upbringing, he waved at his record shelf, with its alphabetized recordings from Cannonball Adderley to Attila Zoller. He had listened to the hard bop recordings of his era: the Blue Notes, Riverside, and Prestige recordings. Still, starting at age 11, he was also playing the blues, imitating the sounds of John Hurt, Fred McDowell, and Gary Davis.

The Boston music scene has suffered another loss with the passing of the beautifully accomplished guitarist, author, and (at the Berklee College of Music) teacher, Garrison Fewell. He was 61. Last year we talked in his Somerville apartment. We were in his music room, where he sat in front of a wall of LPs. “Vinyl makes friends,” he joked to me. (Over the years we had spent afternoons together hunting for records in Manhattan.) His career was varied and in some ways unexpected. Its beginnings, though, were almost inevitable. When I asked about his musical upbringing, he waved at his record shelf, with its alphabetized recordings from Cannonball Adderley to Attila Zoller. He had listened to the hard bop recordings of his era: the Blue Notes, Riverside, and Prestige recordings. Still, starting at age 11, he was also playing the blues, imitating the sounds of John Hurt, Fred McDowell, and Gary Davis. Early on in his career, alto saxophonist Ornette Coleman, recorded an album entitled, The Shape of Jazz To Come. It might have seemed like an expression of youthful arrogance – Coleman was 29 at the time – but actually, the title was prophetic. Coleman is the creator of a concept of music called “harmolodic,” a musical form which is equally applicable as a life philosophy. The richness of harmolodics derives from the unique interaction between the players. Breaking out of the prison bars of rigid meters and conventional harmonic or structural expectations, harmolodic musicians improvise equally together in what Coleman calls compositional improvisation, while always keeping deeply in tune with the flow, direction and needs of their fellow players. In this process, harmony becomes melody becomes harmony. Ornette describes it as “Removing the caste system from sound.” On a broader level, harmolodics equates with the freedom to be as you please, as long as you listen to others and work with them to develop your own individual harmony.

Early on in his career, alto saxophonist Ornette Coleman, recorded an album entitled, The Shape of Jazz To Come. It might have seemed like an expression of youthful arrogance – Coleman was 29 at the time – but actually, the title was prophetic. Coleman is the creator of a concept of music called “harmolodic,” a musical form which is equally applicable as a life philosophy. The richness of harmolodics derives from the unique interaction between the players. Breaking out of the prison bars of rigid meters and conventional harmonic or structural expectations, harmolodic musicians improvise equally together in what Coleman calls compositional improvisation, while always keeping deeply in tune with the flow, direction and needs of their fellow players. In this process, harmony becomes melody becomes harmony. Ornette describes it as “Removing the caste system from sound.” On a broader level, harmolodics equates with the freedom to be as you please, as long as you listen to others and work with them to develop your own individual harmony. Los Angeles proved to be the laboratory for what came to be called free jazz. There began to gather around Ornette a core of players who would figure largely in his life: a lanky teenage trumpeter, Don Cherry and a cherubic double bass player with a pensive, muscular style named Charlie Haden, drummers Ed Blackwell and Billy Higgins also joined the intense exploratory rehearsals in which Coleman was honing his vocabulary on a plastic sax, despite the lack of live gigs.

Los Angeles proved to be the laboratory for what came to be called free jazz. There began to gather around Ornette a core of players who would figure largely in his life: a lanky teenage trumpeter, Don Cherry and a cherubic double bass player with a pensive, muscular style named Charlie Haden, drummers Ed Blackwell and Billy Higgins also joined the intense exploratory rehearsals in which Coleman was honing his vocabulary on a plastic sax, despite the lack of live gigs. Coleman’s 1986 collaboration with jazz-rock guitarist Pat Metheny, Song X led to a tour and a new audience. Ornette moved into the broader public consciousness in the late 80s by performing and recording with the Grateful Dead and their hippy virtuoso guitarist, Jerry Garcia. The affection and respect which Coleman and the late Garcia had for one another was captured in the sessions for 1988’s Virgin Beauty (CBS/Portrait).

Coleman’s 1986 collaboration with jazz-rock guitarist Pat Metheny, Song X led to a tour and a new audience. Ornette moved into the broader public consciousness in the late 80s by performing and recording with the Grateful Dead and their hippy virtuoso guitarist, Jerry Garcia. The affection and respect which Coleman and the late Garcia had for one another was captured in the sessions for 1988’s Virgin Beauty (CBS/Portrait). Gunther Schuller, a composer, conductor, author and teacher who coined the term Third Stream to describe music that drew on the forms and resources of both classical and jazz, and who was its most important composer, died on Sunday in Boston. He was 89.

Gunther Schuller, a composer, conductor, author and teacher who coined the term Third Stream to describe music that drew on the forms and resources of both classical and jazz, and who was its most important composer, died on Sunday in Boston. He was 89. Wendell Holmes, vocalist, guitarist, pianist and songwriter of the critically acclaimed soul/blues band The Holmes Brothers, died on Friday, June 19 at his home in Rosedale, Maryland of complications due to pulmonary hypertension. Earlier this week, Wendell addressed his fans and friends in an open letter as he moved into hospice care. He was 71.

Wendell Holmes, vocalist, guitarist, pianist and songwriter of the critically acclaimed soul/blues band The Holmes Brothers, died on Friday, June 19 at his home in Rosedale, Maryland of complications due to pulmonary hypertension. Earlier this week, Wendell addressed his fans and friends in an open letter as he moved into hospice care. He was 71.