Author Archive

Thursday, October 2nd, 2014

The premier blues shouter of the postwar era, Big Joe Turner’s roar could rattle the very foundation of any gin joint he sang within — and that’s without a microphone. Turner was a resilient figure in the history of blues — he effortlessly spanned boogie-woogie, jump blues, even the first wave of rock & roll, enjoying great success in each genre. The premier blues shouter of the postwar era, Big Joe Turner’s roar could rattle the very foundation of any gin joint he sang within — and that’s without a microphone. Turner was a resilient figure in the history of blues — he effortlessly spanned boogie-woogie, jump blues, even the first wave of rock & roll, enjoying great success in each genre.

Turner, whose powerful physique certainly matched his vocal might, was a product of the swinging, wide-open Kansas City scene. Even in his teens, the big-boned Turner looked entirely mature enough to gain entry to various K.C. niteries. He ended up simultaneously tending bar and singing the blues before hooking up with boogie piano master Pete Johnson during the early ’30s. Theirs was a partnership that would endure for 13 years.

The pair initially traveled to New York at John Hammond’s behest in 1936. On December 23, 1938, they appeared on the fabled Spirituals to Swing concert at Carnegie Hall on a bill with Big Bill Broonzy, Sonny Terry, the Golden Gate Quartet, and Count Basie. Turner and Johnson performed “Low Down Dog” and “It’s All Right, Baby” on the historic show, kicking off a boogie-woogie craze that landed them a long-running slot at the Cafe Society (along with piano giants Meade Lux Lewis and Albert Ammons).

As 1938 came to a close, Turner and Johnson waxed the thundering “Roll ‘Em Pete” for Vocalion. It was a thrilling up-tempo number anchored by Johnson’s crashing 88s, and Turner would re-record it many times over the decades. Turner and Johnson waxed their seminal blues “Cherry Red” the next year for Vocalion with trumpeter Hot Lips Page and a full combo in support. In 1940, the massive shouter moved over to Decca and cut “Piney Brown Blues” with Johnson rippling the ivories. But not all of Turner’s Decca sides teamed him with Johnson; Willie “The Lion” Smith accompanied him on the mournful “Careless Love,” while Freddie Slack’s Trio provided backing for “Rocks in My Bed” in 1941.

Turner ventured out to the West Coast during the war years, building quite a following while ensconced on the L.A. circuit. In 1945, he signed on with National Records and cut some fine small combo platters under Herb Abramson’s supervision. Turner remained with National through 1947, belting an exuberant “My Gal’s a Jockey” that became his first national R&B smash. Contracts didn’t stop him from waxing an incredibly risqué two-part “Around the Clock” for the aptly named Stag imprint (as Big Vernon!) in 1947. There were also solid sessions for Aladdin that year that included a wild vocal duel with one of Turner’s principal rivals, Wynonie Harris, on the ribald two-part “Battle of the Blues.”

Few West Coast indie labels of the late ’40s didn’t boast at least one or two Turner titles in their catalogs. The shouter bounced from RPM to Down Beat/Swing Time to MGM (all those dates were anchored by Johnson’s piano) to Texas-based Freedom (which moved some of their masters to Specialty) to Imperial in 1950 (his New Orleans backing crew there included a young Fats Domino on piano). But apart from the 1950 Freedom 78, “Still in the Dark,” none of Turner’s records were selling particularly well. When Atlantic Records bosses Abramson and Ahmet Ertegun fortuitously dropped by the Apollo Theater to check out Count Basie’s band one day, they discovered that Turner had temporarily replaced Jimmy Rushing as the Basie band’s frontman, and he was having a tough go of it. Atlantic picked up his spirits by picking up his recording contract, and Turner’s heyday was about to commence. Few West Coast indie labels of the late ’40s didn’t boast at least one or two Turner titles in their catalogs. The shouter bounced from RPM to Down Beat/Swing Time to MGM (all those dates were anchored by Johnson’s piano) to Texas-based Freedom (which moved some of their masters to Specialty) to Imperial in 1950 (his New Orleans backing crew there included a young Fats Domino on piano). But apart from the 1950 Freedom 78, “Still in the Dark,” none of Turner’s records were selling particularly well. When Atlantic Records bosses Abramson and Ahmet Ertegun fortuitously dropped by the Apollo Theater to check out Count Basie’s band one day, they discovered that Turner had temporarily replaced Jimmy Rushing as the Basie band’s frontman, and he was having a tough go of it. Atlantic picked up his spirits by picking up his recording contract, and Turner’s heyday was about to commence.

At Turner’s first Atlantic date in April of 1951, he imparted a gorgeously world-weary reading to the moving blues ballad “Chains of Love” (co-penned by Ertegun and pianist Harry Van Walls) that restored him to the uppermost reaches of the R&B charts. From there, the hits came in droves: “Chill Is On,” “Sweet Sixteen” (yeah, the same downbeat blues B.B. King’s usually associated with; Turner did it first), and “Don’t You Cry” were all done in New York, and all hit big.

Turner had no problem whatsoever adapting his prodigious pipes to whatever regional setting he was in. In 1953, he cut his first R&B chart-topper, the storming rocker “Honey Hush” (later covered by Johnny Burnette and Jerry Lee Lewis), in New Orleans, with trombonist Pluma Davis and tenor saxman Lee Allen in rip-roaring support. Before the year was through, he stopped off in Chicago to record with slide guitarist Elmore James’ considerably rougher-edged combo and hit again with the salacious “T.V. Mama.”

Prolific Atlantic house writer Jesse Stone was the source of Turner’s biggest smash of all, “Shake, Rattle and Roll,” which proved his second chart-topper in 1954. With the Atlantic braintrust reportedly chiming in on the chorus behind Turner’s rumbling lead, the song sported enough pop possibilities to merit a considerably cleaned-up cover by Bill Haley & the Comets (and a subsequent version by Elvis Presley that came a lot closer to the original leering intent).

Suddenly, at the age of 43, Turner was a rock star. His jumping follow-ups — “Well All Right,” “Flip Flop and Fly,” “Hide and Seek,” “Morning, Noon and Night,” “The Chicken and the Hawk” — all mined the same good-time groove as “Shake, Rattle and Roll,” with crisp backing from New York’s top session aces and typically superb production by Ertegun and Jerry Wexler.

Turner turned up on a couple episodes of the groundbreaking TV program Showtime at the Apollo during the mid-’50s, commanding center stage with a joyous rendition of “Shake, Rattle and Roll” in front of saxman Paul “Hucklebuck” Williams’ band. Nor was the silver screen immune to his considerable charms: Turner mimed a couple of numbers in the 1957 film Shake Rattle & Rock (Fats Domino and Mike “Mannix” Connors also starred in the flick).

Updating the pre-war number “Corrine Corrina” was an inspired notion that provided Turner with another massive seller in 1956. But after the two-sided hit “Rock a While”/”Lipstick Powder and Paint” later that year, his Atlantic output swiftly faded from commercial acceptance. Atlantic’s recording strategy wisely involved recording Turner in a jazzier setting for the adult-oriented album market; to that end, a Kansas City-styled set (with his former partner Johnson at the piano stool) was laid down in 1956 and remains a linchpin of his legacy.

Turner stayed on at Atlantic into 1959, but nobody bought his violin-enriched remake of “Chains of Love” (on the other hand, a revival of “Honey Hush” with King Curtis blowing a scorching sax break from the same session was a gem in its own right). The ’60s didn’t produce too much of lasting substance for the shouter — he actually cut an album with longtime admirer Haley and his latest batch of Comets in Mexico City in 1966!

Blues Train But by the tail end of the decade, Turner’s essential contributions to blues history were beginning to receive proper recognition; he cut LPs for BluesWay and Blues Time. During the ’70s and ’80s, Turner recorded prolifically for Norman Granz’s jazz-oriented Pablo label. These were super-relaxed impromptu sessions that often paired the allegedly illiterate shouter with various jazz luminaries in what amounted to loosely run jam sessions. Turner contentedly roared the familiar lyrics of one or another of his hits, then sat back while somebody took a lengthy solo. Other notable album projects included a 1983 collaboration with Roomful of Blues, Blues Train, for Muse. Although health problems and the size of his humongous frame forced him to sit down during his latter-day performances, Turner continued to tour until shortly before his death in 1985. They called him the Boss of the Blues, and the appellation was truly a fitting one: when Turner shouted a lyric, you were definitely at his beck and call.

By Bill Dahl

Originally published on www.allmusic.com

Posted in Artist of the Month | 5 Comments »

Tuesday, September 16th, 2014

Legendary pianist Joe Sample, who was known for pushing the boundaries of jazz music, passed away Friday night in his hometown of Houston at the age of 75, his family announced on Facebook. Legendary pianist Joe Sample, who was known for pushing the boundaries of jazz music, passed away Friday night in his hometown of Houston at the age of 75, his family announced on Facebook.

The keyboardist, who collaborated with artists like Miles Davis, B.B. King, Marvin Gaye and Steely Dan, was best known as the founder of the Crusaders, a quartet that popularized a soulful, funky sound in the 1960s and ’70s.

Sample’s ear for grooves resulted in the sampling of many of his songs by hip-hop artists, the most famous of which, “In All My Wildest Dreams,” was sampled by Tupac in his track, “Dear Mama.”

Sample said he made up his mind at age 14 to be a musician.

“Music was the only fun anyone had in their life at that time,” Sample told the magazine Wax Poetics, describing how his upbringing in Segregation-era Houston made his genre-bending music second nature. “Everything about the history of my family has always been mixed: the races, the food, the language — everything. It’s very natural.”

Originally published at nydailynews.com

Posted in Music News | 3 Comments »

Wednesday, September 10th, 2014

Gerald Wilson, a bandleader, trumpeter, composer, arranger and educator whose multifaceted career reached from the swing era of the 1930s to the diverse jazz sounds of the 21st century, has died. He was 96. Gerald Wilson, a bandleader, trumpeter, composer, arranger and educator whose multifaceted career reached from the swing era of the 1930s to the diverse jazz sounds of the 21st century, has died. He was 96.

Wilson, who had been in declining health, died Monday at his home in Los Angeles, two weeks after contracting pneumonia, said his son, jazz guitarist Anthony Wilson.

In a lifetime that spanned a substantial portion of the history of jazz, Wilson’s combination of articulate composition skills with a far-reaching creative vision carried him successfully through each of the music’s successive new evolutions.

He led his own Gerald Wilson Orchestras — initially for a few years in the mid-1940s, then intermittently in every succeeding decade — recording with stellar assemblages of players, continuing to perform live, well after big jazz bands had been largely eclipsed by small jazz groups and the ascendancy of rock music.

Seeing and hearing Wilson lead his ensembles — especially in his later years — was a memorable experience for jazz fans. Garbed in well tailored suits, his long white hair flowing, Wilson shaped the music with dynamic movements and the elegant grace of a modern dancer.

Asked about his unique style of conducting by Terry Gross on the NPR show “Fresh Air” in 2006, he replied: It’s “different from any style you’ve ever seen before. I move. I choreograph the music as I conduct. You see, I point it out, everything you’re to listen to.”

That approach to conducting, combined with the dynamic quality of his music, had a significant impact on the players in his ensembles.

“There’s no way you can sit in Gerald’s band and sit on the back of your chair,” bandleader/arranger John Clayton told the Detroit Free Press. “He handles the orchestra in a very wise and experienced craftsman sort of way. The combination of the heart and the craft is in perfect balance.”

Wilson’s mastery of the rich potential in big jazz band instrumentation was evident from the beginning. Although he was not pleased with his first arrangement — a version of the standard “Sometimes I’m Happy” written in 1939, when he was playing trumpet in the Jimmie Lunceford band — he was encouraged by Lunceford and his fellow players to write more. “Hi Spook,” his first original composition for big band, followed and was quickly added to the Lunceford repertoire. Soon after, Wilson wrote a brightly swinging number titled “Yard Dog Mazurka” — a popular piece that eventually became the inspiration for the Stan Kenton hit “Intermission Riff.” It was the beginning of an imaginative flow of music that would continue well into the 21st century.

Always an adventurous composer, Wilson’s big band music often had a personal touch, aimed at displaying the talents of a specific player, or inspired by many of his family members. After marrying his Mexican American wife, Josefina Villasenor Wilson, he was drawn to music possessing Spanish/Mexican qualities. His “Viva Tirado,” dedicated to bullfighter Jose Ramon Tirado, became a hit for the Latin rock group El Chicano and was one of several compositions celebrating the achievements of stars of the bullring.

“His pieces are all extended, with long solos and long backgrounds,” musician/jazz historian Loren Schoenberg told the New York Times in 1988. “They’re almost hypnotic. Most are seven to 10 minutes long. Only a master can keep the interest going that long, and he does.”

In addition to his compositions, Wilson was an arranger with the ability to craft songs to the styles of individual performers, as well as the musical characteristics of other orchestras. It was a skill that kept him busy during the periods when he was not concentrating on leading his own groups.

“I may have done more numbers and orchestrations than any other black jazz artist in the world,” he told the Los Angeles Sentinel. “I did 60-something for Ray Charles. I did his first and second country-western album. I wrote a lot of music for Count Basie, eight numbers for his first Carnegie Hall concert,” he said.

He also provided arrangements and compositions for such major jazz artists as Duke Ellington, Dinah Washington, Billie Holiday, Sarah Vaughan, Dizzy Gillespie, Ella Fitzgerald, Nancy Wilson and others, as well as — from various genres — Bobby Darin, Harry Belafonte, B.B. King and Les McCann.

Wilson’s longstanding desire to compose for symphony orchestra came to fruition with “Debut: 5/21/72,” commissioned for the Los Angeles Philharmonic in 1972 by the Philharmonic’s musical director, Zubin Mehta. His “Theme for Monterey,” composed as a commission by the Monterey Jazz Festival in 1997, received two Grammy nominations. In 2009, on his 91st birthday, he conducted the premiere of his six-movement work, “Detroit Suite,” a tribute to the city in which his music career began, commissioned by the Detroit International Jazz Festival.

Gerald Stanley Wilson was born Sept. 4, 1918, in Shelby, Miss. He began to take piano lessons with his mother, a schoolteacher, when he was 6. After purchasing an instrument from the Sears Roebuck catalog for $9.95, he took up the trumpet at age 11. The absence of a high school for African Americans in segregated Shelby made it necessary for him to begin his secondary school studies in Memphis. But a trip with his mother to the Chicago World’s Fair in 1933 stimulated a desire to move north, and he was sent to live with friends in Detroit, where he attended and graduated from the highly regarded Cass Technical High School.

An adept trumpeter while still in his teens, Wilson played at Detroit’s Plantation Club before joining the Chic Carter Band touring band. In 1939 he replaced trumpeter-arranger Sy Oliver in the Jimmy Lunceford Orchestra, then one of the nation’s most prominent swing bands.

Wilson served in the U.S. Navy at the Great Lakes Naval Training Center during World War II, then moved to Los Angeles, forming his own big band in 1944. Despite the band’s almost immediate success, with nearly 50 recorded pieces and a string of national bookings in its first years of existence, Wilson was not satisfied with his own personal level of craftsmanship. He disbanded the ensemble to spend a few years filling in what he believed were gaps in his music education. He also went on the road with the Count Basie Band and Dizzy Gillespie’s group.

Throughout the 1950s and ’60s, Wilson was an established participant in L.A.’s busy music scene, arranging, composing for jazz and pop singers, big bands, films and television, while continuing to be active with his own orchestra. Eager to pass on his knowledge and experience, he taught jazz courses at what is now Cal State Northridge, Cal State L.A. and UCLA, and had a radio program on KBCA-FM (105.1) from 1969 to 1976.

As he moved into his 60s, Wilson viewed the commercial activity of his earlier years as the foundation that allowed him to concentrate on his creative efforts.

He had worked hard, he told the Boston Globe, so that in his later years he would no longer “have to go hustling any jobs. I have written for the symphony. I have written for the movies, and I have written for television. I arrange anything. I wanted to do all these things. I’ve done that. Now I’m doing exactly what I want, musically, and I do it when I please. I’m a musician, but first and foremost, a jazz musician.”

Besides his wife and his son, Wilson is survived by daughters Jeri and Nancy Jo, and four grandchildren.

Originally published in the LA Times.

Posted in Music News | 7 Comments »

Monday, September 1st, 2014

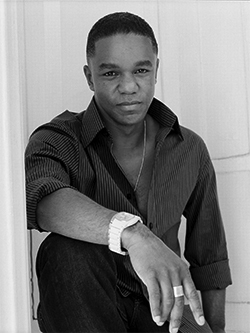

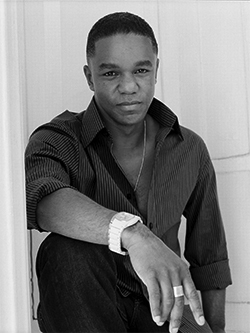

Vibraphonist/percussionist Stefon Harris originally planned to pursue his musical ambitions as a member of the New York Philharmonic, but his first exposure to the music of Charlie Parker convinced him to play jazz instead. Emerging during the mid-’90s on sessions led by Steve Turre, Charlie Hunter, and others, he made his solo debut in 1998 with the Blue Note release A Cloud of Red Dust. The Grammy-nominated Black Action Figure followed a year later. A collaboration with labelmate, pianist Jacky Terrasson, was a defining moment for Harris. Their week-long showcase at the Village Vanguard in summer 2001 was a success, encouraging both artists to work together in the studio. Kindred, a set of standards woven around a few original tracks, was issued in 2001. Vibraphonist/percussionist Stefon Harris originally planned to pursue his musical ambitions as a member of the New York Philharmonic, but his first exposure to the music of Charlie Parker convinced him to play jazz instead. Emerging during the mid-’90s on sessions led by Steve Turre, Charlie Hunter, and others, he made his solo debut in 1998 with the Blue Note release A Cloud of Red Dust. The Grammy-nominated Black Action Figure followed a year later. A collaboration with labelmate, pianist Jacky Terrasson, was a defining moment for Harris. Their week-long showcase at the Village Vanguard in summer 2001 was a success, encouraging both artists to work together in the studio. Kindred, a set of standards woven around a few original tracks, was issued in 2001.

The Grand Unification Theory pushed Harris’ boundaries yet again. The 12-piece ensemble jazz suite appeared in 2003, eventually earning Harris the prestigious Martin E. Segal Award from Jazz at Lincoln Center. Dates with the Kenny Barron Quintet coincided with the spring 2004 release of Evolution. African Tarantella appeared in 2006, followed three years later by Urbanus in 2009.

Originally published on allmusic.com

Photo sources:

- Photo on homepage

- Photo above

Posted in Artist of the Month | 9 Comments »

Friday, August 22nd, 2014

In his third year as the Detroit Jazz Festival Artistic Director, Chris Collins has cultivated another amazing lineup for this year’s Labor Day weekend performances. The vision for 2014 is to continue to create musical experiences and collaborations that articulate “Jazz Speaks for Life,” the important words spoken by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. at the 1964 Berlin Jazz Festival. Once again, musicians from around the world and right here in Detroit as well, will come together to weave deep, meaningful stories through their music that are at the very root of what makes jazz an art form that imitates, creates and expands our collective musical and life experiences.

Click here to view the lineup & download the schedule.

Posted in Music News | 5 Comments »

Friday, August 1st, 2014

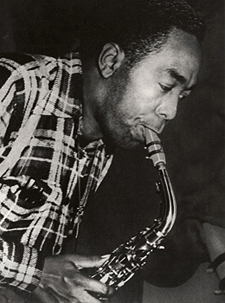

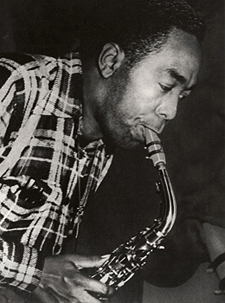

Charlie Parker was born in Kansas City, Kansas and raised in Kansas City, Missouri, the only child of Charles and Addie Parker. Parker attended Lincoln High School. He enrolled in September 1934 and withdrew in December 1935 about the time he joined the local Musicians Union. Charlie Parker was born in Kansas City, Kansas and raised in Kansas City, Missouri, the only child of Charles and Addie Parker. Parker attended Lincoln High School. He enrolled in September 1934 and withdrew in December 1935 about the time he joined the local Musicians Union.

Parker began playing the saxophone at age 11 and at age 14 joined his school’s band using a rented school instrument. One story holds that, without formal training, he was terrible, and thrown out of the band. Experiencing periodic setbacks of this sort, at one point he broke off from his constant practicing.

In early 1936, it has been stated that Parker participated in a ‘cutting contest’ that included Jo Jones on drums, who tossed a cymbal at Parker’s feet in impatience with his playing. Groups led by Count Basie and Bennie Moten were the leading Kansas City ensembles, and undoubtedly influenced Parker. He continued to play with local bands in jazz clubs around Kansas City, Missouri, where he perfected his technique with the assistance of Buster Smith, whose dynamic transitions to double and triple time certainly influenced Parker’s developing style.

As a teenager, Parker developed a morphine addiction while in hospital after an automobile accident, and subsequently became addicted to heroin. Heroin would haunt him throughout his life and ultimately contribute to his death.

In 1939, Parker moved to New York City. There he pursued a career in music, but held several other jobs as well. He worked for $9 a week as a dishwasher at Jimmie’s Chicken Shack where pianist Art Tatum performed. Parker’s later style in some ways recalled Tatum’s, with dazzling, high-speed arpeggios and sophisticated use of harmony.

On November 26, 1945 Parker led a record date for the Savoy label, marketed as the “greatest Jazz session ever.” The tracks recorded during this session include “Ko-Ko” (based on the chords of “Cherokee”), “Now’s the Time” (a twelve bar blues incorporating a riff later used in the late 1949 R&B dance hit “The Hucklebuck”), “Billie’s Bounce”, and “Thriving on a Riff”.

On November 30, 1949, Norman Granz arranged for Parker to record an album of ballads with a mixed group of jazz and chamber orchestra musicians. Six master takes from this session comprised the album Bird With Strings: “Just Friends”, “Everything Happens to Me”, “April in Paris”, “Summertime”, “I Didn’t Know What Time It Was”, and “If I Should Lose You.” The sound of these recordings is unique in Parker’s catalog. The lush string arrangements recall Tchaikovsky in their dramatic sweep, and the rhythm section provides a delicate swing under Parker’s improvisation, blending perfectly with the orchestra. Parker’s improvisations are, relative to his usual work, more distilled and economical. His tone is darker and softer than on his small-group recordings, and the majority of his lines are beautiful embellishments on the original melodies rather than harmonically based improvisations. He is always tasteful and brimming with eloquent expression. These are among the few recordings Parker made during a brief period when he was able to control his heroin habit, and his sobriety and clarity of mind are evident in his playing. Parker stated that, of his own records, Bird With Strings was his favorite.

In 1953, Parker performed at Massey Hall in Toronto, Canada, joined by Gillespie, Mingus, Bud Powell and Max Roach. Unfortunately, the concert clashed with a televised heavyweight boxing match between Rocky Marciano and Jersey Joe Walcott and as a result was poorly attended. Thankfully, Mingus recorded the concert, and the album Jazz at Massey Hall is often cited as one of the finest recordings of a live jazz performance, with the saxophonist credited as “Charley Chan” for contractual reasons.

Parker died in the suite of his friend and patron Nica de Koenigswarter at the Stanhope Hotel in New York City while watching Tommy Dorsey on television. Though the official causes of death were lobar pneumonia and a bleeding ulcer, Parker’s demise was undoubtedly hastened by his drug and alcohol abuse. The coroner who performed his autopsy mistakenly estimated Parker’s 34-year-old body to be between 50 and 60 years of age. Parker was buried at Lincoln Cemetery in Kansas City, Missouri.

Shortly after Parker died, graffiti began appearing around New York with the words ‘Bird Lives.’

Posted in Artist of the Month | 6 Comments »

Wednesday, July 30th, 2014

On Monday, August 4, WNCU will offer an updated program schedule. The changes are below:

- Weekdays will have mainstream jazz from 7 a.m. until 7 p.m. At 7 p.m., tune into Democracy Now.

- From 8 – 10 p.m., Ben Boddie will be our new evening host. Ben is a long time jazz fan and historian, and has been hosting jazz radio for many years.

- The Saturday schedule has no changes. All the programs and times will remain the same.

- On Sunday nights, State of the Reunion will move to 7 p.m., Making Contact to 9 p.m. and Cambridge Forum to 9:30 p.m. All other programs will be unchanged.

Posted in Music News | 1 Comment »

Monday, July 28th, 2014

WNCU 90.7 FM and North Carolina Central University will open the radio station to the public on August 13, 2014, for an open house reception. This is the first in a series of activities in celebration of WNCU’s 20th anniversary leading up to August 2015. The ceremony will feature elected officials, high profile NCCU officials, giveaways and live music from NCCU’s own Robert Trowers, co-host of Eagle Jazz, on the air at WNCU. Join the staff and management in the lobby of the Farrison-Newton Communications Building at 1801 Fayetteville Street in Durham.

The evening kicks off at 6 p.m. with an introduction by WNCU General Manager Lackisha Freeman. More than a dozen well-known names and faces will wish WNCU a happy anniversary. The station will also open for tours.

The anniversary celebration continues throughout 2014-15, with a wide variety of events and activities that underscore WNCU’s impact on Durham and surrounding communities, as well as the history and enduring appeal of public radio. Among the year’s highlights:

- August 18, 2014 – Durham, NC WNCU Partnership with the Blue Note Grill

- August 29, 2014 – Durham, NC Cuban Revolution Remote Broadcast

- September 13-14, 2014 – Hillsborough Jazz Festival, 12 – 6 p.m.

- September 18, 2014 – Durham, NC WNCU Panel Discussion, 11 a.m. – noon

- September 20-21, 2014 – Durham, NC Centerfest, 10 a.m. – 6 p.m.

- September 22, 2014 – Durham Blue Note Grill Jazz Jam

- September 26, 2014 – Durham, NC Cuban Revolution Remote Broadcast, 8 – 10 p.m.

- October 15-24, 2014 Durham, NC WNCU Fall Fest

- October 11, 2014 – Durham, NC Blue Note Grill, 8 – 11 p.m.

- October 31, 2014 – Durham, NC Cuban Revolution Remote, 8 – 10 p.m.

- November 11, 2014 – Durham, NC WNCU Food Drive

- November 21, 2014 – Durham, NC Cuban Revolution Remote, 8 – 10 p.m.

- December 12, 2014 – Durham, NC Blue Note Grill Remote Ann McCue, 9 p.m. – midnight

WNCU will host several other events over the course of the celebratory year.

“This yearlong celebration is a tribute to our listening audience, corporate sponsors and our university for their support throughout the years,” said WNCU general manager Lackisha Freeman. “Please come join us in celebrating 20 years of presenting and preserving great music, news and information in the Triangle community and surrounding areas. This is truly an exciting time for WNCU and a pivotal moment in our history as we catapult into many more years of success. We are the most listened to jazz station in the Triangle. I thank everyone for keeping WNCU relevant and pushing to keep this public radio station around for future generations.” Freeman has been the general manager of WNCU since September of 2010.

Before Freeman, Edith Thorpe was the general manager. She came to WNCU in April of 2001. “It was sheer joy to share such an artistic and cultural gift worldwide and to break ground on some of the most interesting and provocative news and public affairs programming,” Thorpe said of her time at WNCU. “WNCU was established to share these gifts and I am blessed to have had the pleasure for eight years.”

Donald Baker worked in the early days of WNCU with former NCCU chancellor Tyronza Richmond to lay the framework for the station. Baker, WNCU’s first general manager secured the license for WNCU-FM under then chancellor Julius Chambers. “WNCU is approaching its 20th year because listeners and supporters contribute to support the station,” he said. “The university, licensee to WNCU-FM, is the “silent partner” that created this public venture. As licensee, the university assures that we continue to hear unique voices that share information and alternative perspectives on issues that affect the communities in which we live and work.”

WNCU is a 50,000 watt radio station. Since its debut, the station has consistently fulfilled its mission to provide quality culturally appropriate programming to public radio listeners in the Triangle area. The format of this listener supported public radio station entertains the jazz aficionado, educates the novice jazz listener and disseminates news and information relative to the community-at-large.

MEDIA CONTACTS

Lackisha Freeman, 919-530-7267 lsykes@nccu.edu

Uchenna Bulliner, 919-530-7759 ubulliner@nccu.edu

Kimberley Pierce Cartwright, 919-530-7833kpierce@nccu.edu

[MEDIA NOTE: Most speakers are expected to be available for photos and short interviews after the opening ceremony, from approximately 6:00 p.m. – 7:15 p.m. RSVPs are required by email at kcaldwell@nccu.edu or by phone at 919 530 7445.]

To learn more about WNCU, visit www.wncu.org. Join WNCU of Facebook and Twitter.

Anyone wishing to contribute to WNCU may send gifts or donations to WNCU P.O Box 19875 Durham, NC 27707 or pay on line at www.wncu.org. Click on donations/memberships.

Posted in Music News | 3 Comments »

Tuesday, July 22nd, 2014

Impulse Records is the legendary label that proudly delivered the “new thing” in jazz in the 1960s: avant-garde records from the likes of John Coltrane and Pharaoh Sanders. It also helped jazz cross over to a larger audience; quite a few flower children bought Impulse albums.

But over time, the new thing got old. Impulse went dormant for nearly a decade. When it was time for the label to come out of hibernation in 1986, New Orleans pianist Henry Butler sounded the wake-up call. In the 1990’s Impulse went on hiatus a second time, and now, once again, Henry Butler has been called upon to help reboot the label.

Viper’s Drag, out this month, is Butler’s collaboration with arranger and trumpeter Steven Bernstein. The two joined NPR’s Arun Rath to talk about the new record, and the importance of the Impulse name to jazz history. Hear the radio version at the audio link, and read their edited conversation below.

Originally published at npr.org

Posted in Music News | 9 Comments »

Monday, July 21st, 2014

Come swing with North Carolina Central University’s alumni drummers and Thomas Taylor as they start the school year off with a bang.

Jazz drummer Thomas Taylor and some of the jazz percussion alumni will present a jazz concert and fundraiser in the B.N. Duke Auditorium on the campus of NCCU on Sunday, Aug. 24, at 6 p.m.. In the afternoon, there will be music and percussion-centered workshops starting at 2 p.m., followed by a silent auction starting at 5 p.m. Auction winners will be announced before the final group performs in the evening concert.

NCCU percussion alumni performers include Alvin Atkinson Jr., Larry Q. Draughn Jr., Dan Davis, Jasmine Best and Tyler Leak.

All proceeds will go to the Jazz Studies scholarship fund. The concert is free and open to the public. For more information, contact Thomas Taylor in the Department of Music at NCCU.

Posted in Music News | 5 Comments »

|

The premier blues shouter of the postwar era, Big Joe Turner’s roar could rattle the very foundation of any gin joint he sang within — and that’s without a microphone. Turner was a resilient figure in the history of blues — he effortlessly spanned boogie-woogie, jump blues, even the first wave of rock & roll, enjoying great success in each genre.

The premier blues shouter of the postwar era, Big Joe Turner’s roar could rattle the very foundation of any gin joint he sang within — and that’s without a microphone. Turner was a resilient figure in the history of blues — he effortlessly spanned boogie-woogie, jump blues, even the first wave of rock & roll, enjoying great success in each genre. Few West Coast indie labels of the late ’40s didn’t boast at least one or two Turner titles in their catalogs. The shouter bounced from RPM to Down Beat/Swing Time to MGM (all those dates were anchored by Johnson’s piano) to Texas-based Freedom (which moved some of their masters to Specialty) to Imperial in 1950 (his New Orleans backing crew there included a young Fats Domino on piano). But apart from the 1950 Freedom 78, “Still in the Dark,” none of Turner’s records were selling particularly well. When Atlantic Records bosses Abramson and Ahmet Ertegun fortuitously dropped by the Apollo Theater to check out Count Basie’s band one day, they discovered that Turner had temporarily replaced Jimmy Rushing as the Basie band’s frontman, and he was having a tough go of it. Atlantic picked up his spirits by picking up his recording contract, and Turner’s heyday was about to commence.

Few West Coast indie labels of the late ’40s didn’t boast at least one or two Turner titles in their catalogs. The shouter bounced from RPM to Down Beat/Swing Time to MGM (all those dates were anchored by Johnson’s piano) to Texas-based Freedom (which moved some of their masters to Specialty) to Imperial in 1950 (his New Orleans backing crew there included a young Fats Domino on piano). But apart from the 1950 Freedom 78, “Still in the Dark,” none of Turner’s records were selling particularly well. When Atlantic Records bosses Abramson and Ahmet Ertegun fortuitously dropped by the Apollo Theater to check out Count Basie’s band one day, they discovered that Turner had temporarily replaced Jimmy Rushing as the Basie band’s frontman, and he was having a tough go of it. Atlantic picked up his spirits by picking up his recording contract, and Turner’s heyday was about to commence.

Legendary pianist Joe Sample, who was known for pushing the boundaries of jazz music, passed away Friday night in his hometown of Houston at the age of 75, his family announced on Facebook.

Legendary pianist Joe Sample, who was known for pushing the boundaries of jazz music, passed away Friday night in his hometown of Houston at the age of 75, his family announced on Facebook. Gerald Wilson, a bandleader, trumpeter, composer, arranger and educator whose multifaceted career reached from the swing era of the 1930s to the diverse jazz sounds of the 21st century, has died. He was 96.

Gerald Wilson, a bandleader, trumpeter, composer, arranger and educator whose multifaceted career reached from the swing era of the 1930s to the diverse jazz sounds of the 21st century, has died. He was 96. Vibraphonist/percussionist Stefon Harris originally planned to pursue his musical ambitions as a member of the New York Philharmonic, but his first exposure to the music of Charlie Parker convinced him to play jazz instead. Emerging during the mid-’90s on sessions led by Steve Turre, Charlie Hunter, and others, he made his solo debut in 1998 with the Blue Note release A Cloud of Red Dust. The Grammy-nominated Black Action Figure followed a year later. A collaboration with labelmate, pianist Jacky Terrasson, was a defining moment for Harris. Their week-long showcase at the Village Vanguard in summer 2001 was a success, encouraging both artists to work together in the studio. Kindred, a set of standards woven around a few original tracks, was issued in 2001.

Vibraphonist/percussionist Stefon Harris originally planned to pursue his musical ambitions as a member of the New York Philharmonic, but his first exposure to the music of Charlie Parker convinced him to play jazz instead. Emerging during the mid-’90s on sessions led by Steve Turre, Charlie Hunter, and others, he made his solo debut in 1998 with the Blue Note release A Cloud of Red Dust. The Grammy-nominated Black Action Figure followed a year later. A collaboration with labelmate, pianist Jacky Terrasson, was a defining moment for Harris. Their week-long showcase at the Village Vanguard in summer 2001 was a success, encouraging both artists to work together in the studio. Kindred, a set of standards woven around a few original tracks, was issued in 2001. Charlie Parker was born in Kansas City, Kansas and raised in Kansas City, Missouri, the only child of Charles and Addie Parker. Parker attended Lincoln High School. He enrolled in September 1934 and withdrew in December 1935 about the time he joined the local Musicians Union.

Charlie Parker was born in Kansas City, Kansas and raised in Kansas City, Missouri, the only child of Charles and Addie Parker. Parker attended Lincoln High School. He enrolled in September 1934 and withdrew in December 1935 about the time he joined the local Musicians Union.