Author Archive

Monday, August 8th, 2022

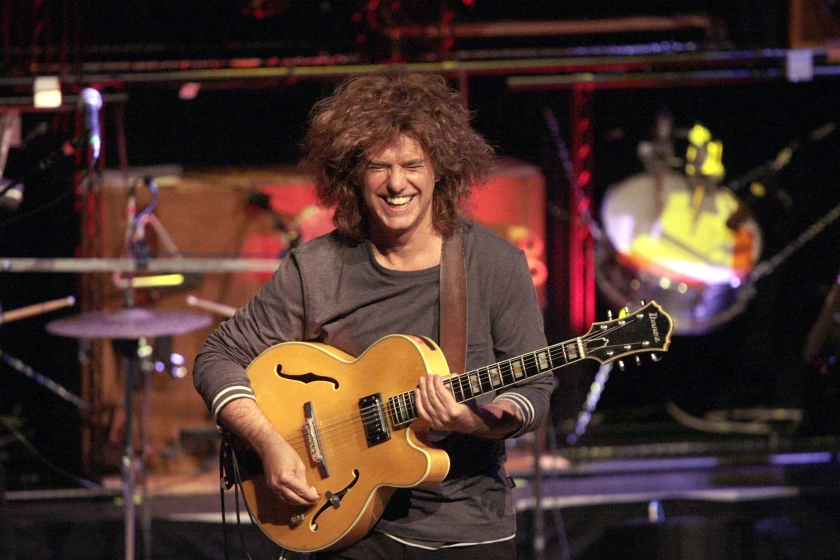

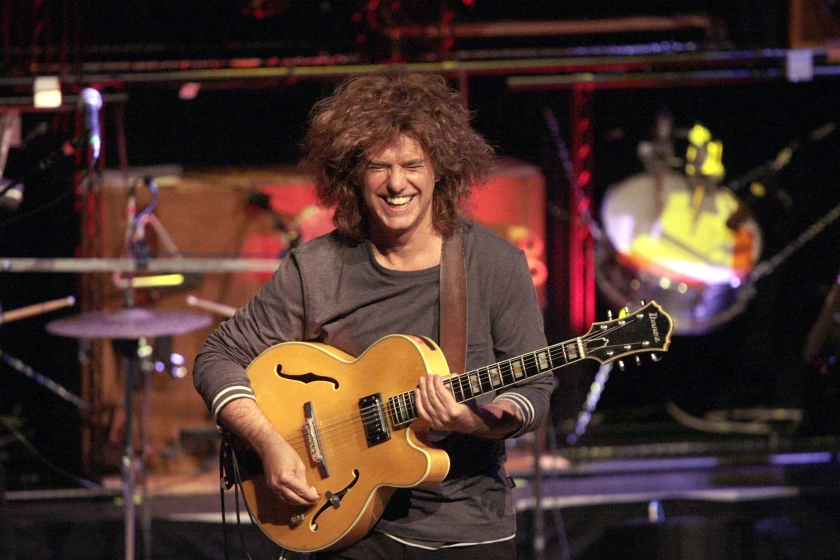

Pat Metheny was born in Kansas City on August 12, 1954 into a musical family. Starting on trumpet at the age of 8, Metheny switched to guitar at age 12. By the age of 15, he was working regularly with the best jazz musicians in Kansas City, receiving valuable on-the-bandstand experience at an unusually young age. Metheny first burst onto the international jazz scene in 1974. Over the course of his three-year stint with vibraphone great Gary Burton, the young Missouri native already displayed his soon-to-become trademarked playing style, which blended the loose and flexible articulation customarily reserved for horn players with an advanced rhythmic and harmonic sensibility – a way of playing and improvising that was modern in conception but grounded deeply in the jazz tradition of melody, swing, and the blues. With the release of his first album, Bright Size Life (1975), he reinvented the traditional “jazz guitar” sound for a new generation of players. Throughout his career, Pat Metheny has continued to re-define the genre by utilizing new technology and constantly working to evolve the improvisational and sonic potential of his instrument. Metheny’S versatility is almost nearly without peer on any instrument. Over the years, he has performed with artists as diverse as Steve Reich to Ornette Coleman to Herbie Hancock to Jim Hall to Milton Nascimento to David Bowie. Metheny’s body of work includes compositions for solo guitar, small ensembles, electric and acoustic instruments, large orchestras, and ballet pieces, with settings ranging from modern jazz to rock to classical. Pat Metheny was born in Kansas City on August 12, 1954 into a musical family. Starting on trumpet at the age of 8, Metheny switched to guitar at age 12. By the age of 15, he was working regularly with the best jazz musicians in Kansas City, receiving valuable on-the-bandstand experience at an unusually young age. Metheny first burst onto the international jazz scene in 1974. Over the course of his three-year stint with vibraphone great Gary Burton, the young Missouri native already displayed his soon-to-become trademarked playing style, which blended the loose and flexible articulation customarily reserved for horn players with an advanced rhythmic and harmonic sensibility – a way of playing and improvising that was modern in conception but grounded deeply in the jazz tradition of melody, swing, and the blues. With the release of his first album, Bright Size Life (1975), he reinvented the traditional “jazz guitar” sound for a new generation of players. Throughout his career, Pat Metheny has continued to re-define the genre by utilizing new technology and constantly working to evolve the improvisational and sonic potential of his instrument. Metheny’S versatility is almost nearly without peer on any instrument. Over the years, he has performed with artists as diverse as Steve Reich to Ornette Coleman to Herbie Hancock to Jim Hall to Milton Nascimento to David Bowie. Metheny’s body of work includes compositions for solo guitar, small ensembles, electric and acoustic instruments, large orchestras, and ballet pieces, with settings ranging from modern jazz to rock to classical.

As well as being an accomplished musician, Metheny has also participated in the academic arena as a music educator. At 18, he was the youngest teacher ever at the University of Miami. At 19, he became the youngest teacher ever at the Berklee College of Music, where he also received an honorary doctorate more than twenty years later (1996). He has also taught music workshops all over the world, from the Dutch Royal Conservatory to the Thelonius Monk Institute of Jazz to clinics in Asia and South America. He has also been a true musical pioneer in the realm of electronic music, and was one of the very first jazz musicians to treat the synthesizer as a serious musical instrument. Years before the invention of MIDI technology, Metheny was using the Synclavier as a composing tool. He has also been instrumental in the development of several new kinds of guitars such as the soprano acoustic guitar, the 42-string Pikasso guitar, Ibanez’s PM-100 jazz guitar, and a variety of other custom instruments. He took the whole instrument development process into a different level with his mechanical, solenoid driven Orchestrion. As well as being an accomplished musician, Metheny has also participated in the academic arena as a music educator. At 18, he was the youngest teacher ever at the University of Miami. At 19, he became the youngest teacher ever at the Berklee College of Music, where he also received an honorary doctorate more than twenty years later (1996). He has also taught music workshops all over the world, from the Dutch Royal Conservatory to the Thelonius Monk Institute of Jazz to clinics in Asia and South America. He has also been a true musical pioneer in the realm of electronic music, and was one of the very first jazz musicians to treat the synthesizer as a serious musical instrument. Years before the invention of MIDI technology, Metheny was using the Synclavier as a composing tool. He has also been instrumental in the development of several new kinds of guitars such as the soprano acoustic guitar, the 42-string Pikasso guitar, Ibanez’s PM-100 jazz guitar, and a variety of other custom instruments. He took the whole instrument development process into a different level with his mechanical, solenoid driven Orchestrion.

It is one thing to attain popularity as a musician, but it is another to receive the kind of acclaim Metheny has garnered from critics and peers. Over the years, Metheny has won countless polls as “Best Jazz Guitarist” and awards, including three gold records for Still Life (Talking), Letter from Home, and Secret Story. He has also won 20 Grammy Awards in 12 different categories including Best Rock Instrumental, Best Contemporary Jazz Recording, Best Jazz Instrumental Solo, Best Instrumental Composition. The Pat Metheny Group won an unprecedented seven consecutive Grammies for seven consecutive albums. Metheny has spent most of his life on tour, averaging between 120-240 shows a year since 1974. At the time of this writing, he continues to be one of the brightest stars of the jazz community, dedicating time to both his own projects and those of emerging artists and established veterans alike, helping them to reach their audience as well as realizing their own artistic visions. It is one thing to attain popularity as a musician, but it is another to receive the kind of acclaim Metheny has garnered from critics and peers. Over the years, Metheny has won countless polls as “Best Jazz Guitarist” and awards, including three gold records for Still Life (Talking), Letter from Home, and Secret Story. He has also won 20 Grammy Awards in 12 different categories including Best Rock Instrumental, Best Contemporary Jazz Recording, Best Jazz Instrumental Solo, Best Instrumental Composition. The Pat Metheny Group won an unprecedented seven consecutive Grammies for seven consecutive albums. Metheny has spent most of his life on tour, averaging between 120-240 shows a year since 1974. At the time of this writing, he continues to be one of the brightest stars of the jazz community, dedicating time to both his own projects and those of emerging artists and established veterans alike, helping them to reach their audience as well as realizing their own artistic visions.

Originally published at patmetheny.com

Photo credits:

- Homepage – fyimusicnews.ca

- Above #1 – sandiegouniontribune.com

- Above #2 – wikipedia.org

- Above #3 – nytimes.com

Posted in Artist of the Month | Comments Off on Pat Metheny

Monday, July 4th, 2022

A cornerstone of the Blue Note label roster prior to his tragic demise, Lee Morgan was one of hard bop’s greatest trumpeters, and indeed one of the finest players of the ’60s. An all-around master of his instrument modeled after Clifford Brown, Morgan boasted an effortless, virtuosic technique and a full, supple, muscular tone that was just as powerful in the high register. His playing was always emotionally charged, regardless of the specific mood: cocky and exuberant on uptempo groovers, blistering on bop-oriented technical showcases, sweet and sensitive on ballads. In his early days as a teen prodigy, Morgan was a busy soloist with a taste for long, graceful lines, and honed his personal style while serving an apprenticeship in both Dizzy Gillespie’s big band and Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers. As his original compositions began to take in elements of blues and R&B, he made greater use of space and developed an infectiously funky rhythmic sense. He also found ways to mimic human vocal inflections by stuttering, slurring his articulations, and employing half-valved sound effects. Morgan led his first Blue Note session in 1956 and he would record his first two classic albums for the label during 1957 and 1958: The Cooker and Candy. He broke through to a wider audience with his classic 1963 album Sidewinder, whose club-friendly title track introduced the soulful, boogaloo jazz sound. Toward the end of his career, Morgan was increasingly moving into modal music and free bop, hinting at the avant-garde but remaining grounded in tradition; a sound showcased on his 1970 concert album Live at the Lighthouse. He had already overcome a severe drug addiction, but sadly, he would not live to continue his musical growth; he was shot to death by his common-law wife in 1972. A cornerstone of the Blue Note label roster prior to his tragic demise, Lee Morgan was one of hard bop’s greatest trumpeters, and indeed one of the finest players of the ’60s. An all-around master of his instrument modeled after Clifford Brown, Morgan boasted an effortless, virtuosic technique and a full, supple, muscular tone that was just as powerful in the high register. His playing was always emotionally charged, regardless of the specific mood: cocky and exuberant on uptempo groovers, blistering on bop-oriented technical showcases, sweet and sensitive on ballads. In his early days as a teen prodigy, Morgan was a busy soloist with a taste for long, graceful lines, and honed his personal style while serving an apprenticeship in both Dizzy Gillespie’s big band and Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers. As his original compositions began to take in elements of blues and R&B, he made greater use of space and developed an infectiously funky rhythmic sense. He also found ways to mimic human vocal inflections by stuttering, slurring his articulations, and employing half-valved sound effects. Morgan led his first Blue Note session in 1956 and he would record his first two classic albums for the label during 1957 and 1958: The Cooker and Candy. He broke through to a wider audience with his classic 1963 album Sidewinder, whose club-friendly title track introduced the soulful, boogaloo jazz sound. Toward the end of his career, Morgan was increasingly moving into modal music and free bop, hinting at the avant-garde but remaining grounded in tradition; a sound showcased on his 1970 concert album Live at the Lighthouse. He had already overcome a severe drug addiction, but sadly, he would not live to continue his musical growth; he was shot to death by his common-law wife in 1972.

Edward Lee Morgan was born in Philadelphia on July 10, 1938. He grew up a jazz lover, and his sister apparently gave him his first trumpet at age 14. He took private lessons, developing rapidly, and continued his studies at Mastbaum High School. By the time he was 15, he was already performing professionally on the weekends, co-leading a group with bassist Spanky DeBrest. Morgan also participated in weekly workshops that gave him the chance to meet the likes of Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, and his idol Clifford Brown. After graduating from high school in 1956, Morgan — along with DeBrest — got the chance to perform with Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers when they swung through Philadelphia. Not long after, Dizzy Gillespie hired Morgan to replace Joe Gordon in his big band, and afforded the talented youngster plenty of opportunities to solo, often spotlighting him on the Gillespie signature piece “A Night in Tunisia.” Clifford Brown’s death in a car crash in June 1956 sparked a search for his heir apparent, and the precocious Morgan seemed a likely candidate to many; accordingly, he soon found himself in great demand as a recording artist. His first session as a leader was cut for Blue Note in November 1956, and over the next few months he recorded for Savoy and Specialty as well, often working closely with Hank Mobley or Benny Golson. Later in 1957, he performed as a sideman on John Coltrane’s classic Blue Train, as well as with Jimmy Smith. Edward Lee Morgan was born in Philadelphia on July 10, 1938. He grew up a jazz lover, and his sister apparently gave him his first trumpet at age 14. He took private lessons, developing rapidly, and continued his studies at Mastbaum High School. By the time he was 15, he was already performing professionally on the weekends, co-leading a group with bassist Spanky DeBrest. Morgan also participated in weekly workshops that gave him the chance to meet the likes of Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, and his idol Clifford Brown. After graduating from high school in 1956, Morgan — along with DeBrest — got the chance to perform with Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers when they swung through Philadelphia. Not long after, Dizzy Gillespie hired Morgan to replace Joe Gordon in his big band, and afforded the talented youngster plenty of opportunities to solo, often spotlighting him on the Gillespie signature piece “A Night in Tunisia.” Clifford Brown’s death in a car crash in June 1956 sparked a search for his heir apparent, and the precocious Morgan seemed a likely candidate to many; accordingly, he soon found himself in great demand as a recording artist. His first session as a leader was cut for Blue Note in November 1956, and over the next few months he recorded for Savoy and Specialty as well, often working closely with Hank Mobley or Benny Golson. Later in 1957, he performed as a sideman on John Coltrane’s classic Blue Train, as well as with Jimmy Smith.

Morgan’s early sessions showed him to be a gifted technician who had his influences down pat, but subsequent dates found him coming into his own as a distinctive, original stylist. That was most apparent on the Blue Note classic Candy, a warm standards album completed in 1958 and released to great acclaim. Still only 19, Morgan’s playing was imbued with youthful enthusiasm, but he was also synthesizing his influences into an original sound of his own. Also in 1958, Gillespie’s big band broke up, and Morgan soon joined the third version of Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, which debuted on the classic Moanin’ album later that year. As a leader, Morgan recorded a pair of albums for Vee Jay in 1960, Here’s Lee Morgan and Expoobident, and cut another for Blue Note that year, Lee-Way, with backing by many of the Jazz Messengers. None managed to measure up to Candy, and Morgan, grappling with heroin addiction, wound up leaving the Jazz Messengers in 1961. He returned to his hometown of Philadelphia to kick the habit, and spent most of the next two years away from music, working occasionally with saxophonist Jimmy Heath on a local basis. His replacement in the Jazz Messengers was Freddie Hubbard, who would also become one of the top hard bop trumpeters of the ’60s.

Morgan returned to New York in late 1963, and recorded with Blue Note avant-gardist Grachan Moncur on the trombonist’s debut Evolution. He then recorded a comeback LP for Blue Note called The Sidewinder, prominently featuring the up-and-coming Joe Henderson. The Morgan-composed title track was a funky, danceable groover that drew from soul-jazz, Latin boogaloo, blues, and R&B in addition to Morgan’s trademark hard bop. It was rather unlike anything else he’d cut, and it became a left-field hit in 1964; edited down to a 45 RPM single, it inched into the lower reaches of the pop charts and was licensed for use in a high-profile automobile ad campaign. Its success helped push The Sidewinder into the Top 25 of the pop LP charts, and the Top Ten on the R&B listing. Sales were brisk enough to revive the financially struggling Blue Note label, and likely kept it from bankruptcy; it also led to numerous “Sidewinder”-style grooves popping up on other Blue Note artists’ albums. By the time “The Sidewinder” became a phenomenon, Morgan had rejoined the Jazz Messengers, where he would remain until 1965; there he solidified a long-standing partnership with saxophonist Wayne Shorter. Morgan returned to New York in late 1963, and recorded with Blue Note avant-gardist Grachan Moncur on the trombonist’s debut Evolution. He then recorded a comeback LP for Blue Note called The Sidewinder, prominently featuring the up-and-coming Joe Henderson. The Morgan-composed title track was a funky, danceable groover that drew from soul-jazz, Latin boogaloo, blues, and R&B in addition to Morgan’s trademark hard bop. It was rather unlike anything else he’d cut, and it became a left-field hit in 1964; edited down to a 45 RPM single, it inched into the lower reaches of the pop charts and was licensed for use in a high-profile automobile ad campaign. Its success helped push The Sidewinder into the Top 25 of the pop LP charts, and the Top Ten on the R&B listing. Sales were brisk enough to revive the financially struggling Blue Note label, and likely kept it from bankruptcy; it also led to numerous “Sidewinder”-style grooves popping up on other Blue Note artists’ albums. By the time “The Sidewinder” became a phenomenon, Morgan had rejoined the Jazz Messengers, where he would remain until 1965; there he solidified a long-standing partnership with saxophonist Wayne Shorter.

Morgan followed the most crucial recording of his career with the excellent, more abstract Search for the New Land, which was cut in early 1964, before “The Sidewinder” hit. An advanced modal bop session called Tom Cat was also recorded shortly thereafter, but both were shelved in hopes of scoring another “Sidewinder.” Accordingly, Morgan re-entered the studio in early 1965 to cut The Rumproller, whose Andrew Hill-penned title cut worked territory that was highly similar to Morgan’s breakout hit. Commercial lightning didn’t strike twice, but Morgan continued to record prolifically through 1965, cutting excellent sessions like The Gigolo, Cornbread, and the unissued Infinity. The Gigolo introduced one of Morgan’s best-known originals, the bluesy “Speedball,” while the classic Cornbread featured his ballad masterpiece “Ceora.” Search for the New Land was finally issued in 1966, and it achieved highly respectable sales, reaching the Top 20 of the R&B album charts; both Cornbread and The Gigolo would sell well among jazz audiences when they were released in 1967 and 1968, respectively.

By the time Morgan completed those albums, he had left the Jazz Messengers to begin leading his own groups outside the studio. He was also appearing frequently as a sideman on other Blue Note releases, working most often with tenorman Hank Mobley. Morgan was extraordinarily prolific between 1966 and 1968, cutting around eight albums’ worth of material (though not all of it was released at the time). Highlights included Delightfulee, The Procrastinator, and the decent-selling Caramba!, which nearly made the Top 40 of the R&B album chart. His compositions were increasingly modal and free-form, stretching the boundaries of hard bop; however, his funkier instincts were still evident as well, shifting gradually from boogaloo to early electrified fusion. Morgan’s recording pace tailed off at the end of the ’60s, but he continued to tour with a regular working group that prominently featured saxophonist Bennie Maupin. This band’s lengthy modal explorations were documented on the double-LP Live at the Lighthouse, recorded in Los Angeles in July 1970; it was reissued in 2021 as The Complete Live at the Lighthouse. By the time Morgan completed those albums, he had left the Jazz Messengers to begin leading his own groups outside the studio. He was also appearing frequently as a sideman on other Blue Note releases, working most often with tenorman Hank Mobley. Morgan was extraordinarily prolific between 1966 and 1968, cutting around eight albums’ worth of material (though not all of it was released at the time). Highlights included Delightfulee, The Procrastinator, and the decent-selling Caramba!, which nearly made the Top 40 of the R&B album chart. His compositions were increasingly modal and free-form, stretching the boundaries of hard bop; however, his funkier instincts were still evident as well, shifting gradually from boogaloo to early electrified fusion. Morgan’s recording pace tailed off at the end of the ’60s, but he continued to tour with a regular working group that prominently featured saxophonist Bennie Maupin. This band’s lengthy modal explorations were documented on the double-LP Live at the Lighthouse, recorded in Los Angeles in July 1970; it was reissued in 2021 as The Complete Live at the Lighthouse.

Morgan led what turned out to be the last session of his life in September 1971. On February 19, 1972, he was performing at the New York club Slug’s when he was shot and killed by his common-law wife, Helen More (aka Helen Morgan). Accounts of exactly what happened vary; whether they argued over drugs or Morgan’s fidelity, whether she shot him outside the club or up on the bandstand in front of the audience, jazz lost a major talent. The events of the night and More’s relationship with Morgan were later the subject of Kasper Collin’s acclaimed 2016 documentary film I Called Him Morgan. Despite his extensive recorded legacy, Morgan was only 33 years old. While The Last Session arrived posthumously in 1972, many of the trumpeter’s unreleased Blue Note sessions began to appear in the early ’80s, and his critical standing has hardly diminished a whit.

Orignally published at allmusic.com

Photo credits:

- Home – sfjazz.org

- Above #1 – npr.org

- Above #2 – en.wikipedia.org

- Above #3 – pleasekillme.com

- Above #4 – bluenote.com

Posted in Artist of the Month | Comments Off on Lee Morgan

Sunday, June 5th, 2022

Pianist, composer, Guggenheim Fellow, and educator Geri Allen died on Tuesday, June 27, 2017 from complications of cancer in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She had recently celebrated her 60th birthday. Pianist, composer, Guggenheim Fellow, and educator Geri Allen died on Tuesday, June 27, 2017 from complications of cancer in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She had recently celebrated her 60th birthday.

Hailed as one of the most accomplished pianists and educators of her time, Allen’s most recent position was as Director of Jazz Studies at the University of Pittsburgh. She was especially proud of performing with renowned pianist McCoy Tyner for the last two years, and was also part of two recent groundbreaking trios: ACS (Geri Allen, Terri Lyne Carrington, and Esperanza Spalding) and the MAC Power Trio with David Murray and Carrington – their debut recording Perfection was released on Motéma Music in 2016 to critical acclaim.

“The jazz community will never be the same with the loss of one of our geniuses, Geri Allen. Her virtuosity and musicality are unparalleled,” expressed Carrington upon learning of her passing. “I will miss my sister and friend, but I am thankful for all of the music she made and all of the incredible experiences we had together for over 35 years. She is a true original – a one of kind – never to be forgotten. My heart mourns, but my spirit is filled with the gift of having known and learned from Geri Allen.“

She was the first woman and youngest person to receive the Danish Jazzpar Prize, and was the first recipient of the Soul Train Lady of Soul Award for Jazz. In 2011, she was nominated for an NAACP Award for Timeline, her Tap Quartet project. Over the last few years, Allen served as the program director of NJPAC’s All-Female Jazz Residency, which offered a weeklong one-of-a-kind opportunity for young women, ages 14-25, to study jazz.

Allen was also recently honored to be one of the producers of the expanded and re-mastered recording of Erroll Garner’s The Complete Concert by the Sea, which garnered her an Essence Image Award nomination as well as a GRAMMY® Award-nomination in 2016. She felt strongly that students should have access to this material, and went on to organize a 60th anniversary performance of the material at the 2015 Monterey Jazz Festival with Jason Moran and Christian Sands.

Having grown up in Detroit, a region known for its rich musical history, Allen’s affinity for jazz stemmed from her father’s passion for the music. She began taking lessons at 7-years-old, and started her early music education under the mentorship of trumpeter Marcus Belgrave at the Cass Technical High School. In 1979, she was one of the first to graduate from Howard University with a Bachelor of Arts degree in jazz studies. It was there that she began to embrace music from all cultures that would ultimately influence her work. During that time, she studied with the great Kenny Barron in New York City.

“I first met Geri when she was a student at Howard. She would take the train up to my house in Brooklyn for lessons. Even then it was apparent that Geri heard some things musically that others did not,” Barron reflects. “In 1994 we performed a duo piano concert at the Caramoor Festival in New York and I realized how fearless she was and at the same time how focused she was. It was a lesson that I took to heart. Geri is not only a great musician, composer and pianist, she is a giant and will be sorely missed.”

In New York, Allen met Nathan Davis, a respected educator who encouraged her to attend the University of Pittsburgh where he served as Director for their Jazz Studies department. She followed his advice and earned her Masters Degree in Ethnomusicology in 1982. In 2013, she became their Director of Jazz Studies upon Davis’ retirement.

While at UPITT, Allen’s commitment to community outreach and bridging educational inequities manifested through her pioneering engagement on the research education network of Internet2 and CENIC, where she connected virtually to universities and cultural institutions across the country, collaborating with artists and technologists such as Terri Lyne Carrington, Chris Chafe, George Lewis, Michael Dressen, Jason Moran, Vijay Iyer and the SFJAZZ High School All-Stars.

She was also the musical director of the Mary Lou Williams Collective, recording and performing the music of the great Mary Lou Williams, including her sacred work Mass For Peace. Allen also collaborated with S. Epatha Merkerson and Farah Jasmine Griffin on two music theatre projects: “Great Apollo Women,” which premiered at the legendary Apollo Theatre, and “A Conversation with Mary Lou,” which premiered at the Harlem Stage as an educational component for the Harlem Stage collaboration. The University of Pittsburgh hosted the first ever Mary Lou Williams Cyber Symposium where Vijay Iyer, Jason Moran, and Allen performed a three piano improvisation from Harvard, Columbia and the University of Pittsburgh in real time using Internet2 technology.

Allen was a recent recipient of the Howard University Pinnacle Award presented by Professor Connaitre Miller and Afro Blue. She has served as a faculty member at Howard University, the New England Conservatory, and the University of Michigan where she taught for ten years. In 2014, Allen was presented with an Honorary Doctorate of Music Degree by Berklee College of Music in Boston. The Honorable Congressman John Conyers Jr. presented the 2014 Congressional Black Caucus Foundation Jazz Legacy Award to Allen.

In 1985, Allen released The Printmakers – her debut release as a leader, and one of the hundreds of releases that encompasses her boisterous discography. In 1990, she signed to Blue Note Records and released The Nurturer with mentor Marcus Belgrave, Kenny Garrett, Robert Hurst, Jeff “Tain” Watts and Eli Fountain. This release showcased a more conventional playing style while still maintaining the freedom of improvisation and expression that was so present at the start of her career.

Throughout the late ‘90s and early 2000s, Allen continued to be a pioneer for the genre both as a side-woman and as a leader. Her improvisational virtuosity was displayed on Ornette Coleman’s 1996 release of Sound Museum, her 1988 release The Gathering, and again in 2004 with The Life a Song featuring Dave Holland and Jack DeJohnette. In 2010 her solo piano album, Flying Towards the Sound was critically acclaimed and was rated “Best of 2010” on NPR and DownBeat magazine’s Critics Polls.

Allen’s commissioned work “For the Healing of the Nations” in 2006 was written to pay tribute to the victims, survivors, and family members of the September 11th attacks. This special tribute was performed by the Howard University’s Afro Blue Jazz Choir and included performances from jazz musicians such as Oliver Lake, Craig Harris, Andy Bey, among others. It was also around this time that Allen had been awarded the prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship honoring her prolific role in furthering this creative art form. This allowed her to release the compositions “Refractions” and “Flying Towards the Sound,” as well as three short films under the Motéma Music label. Allen’s commissioned work “For the Healing of the Nations” in 2006 was written to pay tribute to the victims, survivors, and family members of the September 11th attacks. This special tribute was performed by the Howard University’s Afro Blue Jazz Choir and included performances from jazz musicians such as Oliver Lake, Craig Harris, Andy Bey, among others. It was also around this time that Allen had been awarded the prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship honoring her prolific role in furthering this creative art form. This allowed her to release the compositions “Refractions” and “Flying Towards the Sound,” as well as three short films under the Motéma Music label.

In 2008, Allen received the African American Classical Music Award from the Women of the New Jersey chapter of Spelman College as well as “A Salute to African-American Women: Phenomenal Woman” from the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity, Epsilon chapter at the University of Michigan. Allen also performed in a theatrical and musical celebration honoring Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. for the statue unveiling in Washington, DC.

In a career that spanned more than 35 years, she recorded, performed and collaborated with some of the most important artists of our time including Ornette Coleman, Ravi Coltrane, George Shirley, Dewey Redman, Jimmy Cobb, Sandra Turner-Barnes, Charles Lloyd, Marcus Belgrave, Betty Carter, Jason Moran, Lizz Wright, Marian McPartland, Roy Brooks, Vijay Iyer, Charlie Haden, Paul Motian, Laurie Anderson, Terri Lynn Carrington, Esperanza Spalding, Hal Willner, Ron Carter, Tony Williams, Dianne Reeves, Joe Lovano, Dr. Billy Taylor, Carrie Mae Weems, Angélique Kidjo, Mary Wilson and The Supremes, Howard University’s Afro-Blue and many others.

Allen contributed some of the most groundbreaking and forward thinking music of the time. The remarkable pianist leaves behind a wealth of material that will educate future generations of musicians. A mother of three, she credited her family for making it possible for her to maintain such a successful and fruitful career. She was a cutting edge performing artist, and continued to entertain internationally up until her death.

Geri Allen is survived by her father Mount Vernell Allen, Jr., brother Mount Vernell Allen III, and three children: Laila, Wally, and Barbara Antoinette. Funeral arrangements and a memorial service are pending.

Originally published at geriallen.com

Photo credits:

- Home – post-gazette.com

- Above – geriallen.com

Posted in Artist of the Month | Comments Off on Geri Allen

Monday, May 2nd, 2022

Fats Waller, byname of Thomas Wright Waller, (born May 21, 1904, New York City, New York, U.S.—died December 15, 1943, Kansas City, Missouri, U.S.), American pianist and composer who was one of the few outstanding jazz musicians to win wide commercial fame, though this was achieved at a cost of obscuring his purely musical ability under a cloak of broad comedy. Fats Waller, byname of Thomas Wright Waller, (born May 21, 1904, New York City, New York, U.S.—died December 15, 1943, Kansas City, Missouri, U.S.), American pianist and composer who was one of the few outstanding jazz musicians to win wide commercial fame, though this was achieved at a cost of obscuring his purely musical ability under a cloak of broad comedy.

Overcoming opposition from his clergyman father, Waller became a professional pianist at 15, working in cabarets and theatres, and soon became deeply influenced by James P. Johnson, the founder of the stride school of jazz piano. By the late 1920s he was also an established songwriter whose work often appeared in Broadway revues. From 1934 on he made hundreds of recordings with his own small band, in which excellent jazz was mixed with slapstick in a unique blend.

His best-known songs include “Ain’t Misbehavin’,” “Honeysuckle Rose,” and his first success, “Squeeze Me” (1925), written with Clarence Williams. He was the first jazz musician to master the organ, and he appeared in several films, including Stormy Weather (1943). Usually remembered as a genial clown, he is of lasting importance as one of the greatest of all jazz pianists and as a gifted songwriter, whose work in both fields was rhythmically contagious.

Originally published on britannica.com

Photo credits:

- Homepage – syncopatedtimes.com

- Above – britannica.com

Posted in Artist of the Month | Comments Off on Fats Waller

Saturday, April 9th, 2022

Tough times. Billie Holiday knew about them and sang about them. She had a rough start—her mother, Sadie, was only 13 and her father, Clarence Holiday, was 15. Tough times. Billie Holiday knew about them and sang about them. She had a rough start—her mother, Sadie, was only 13 and her father, Clarence Holiday, was 15.

Sadie Fagan had been thrown out of her house and had moved, alone, from Baltimore to Philadelphia. She gave birth to a daughter, Eleanora, on April 7, 1915, and attempted to raise the girl on her own. Clarence was a musician and eventually went on to play guitar and banjo in Fletcher Henderson’s band. The two married for a very short time when Eleanora was 3 years old, then split up for good.

Sadie and young Eleanora did move back to Baltimore for a while, but their fortunes didn’t improve. Eleanora skipped school a lot, was sexually assaulted at age 11, and was then sent to a Catholic reform school. When she was released two years later, mother and daughter both moved to New York City to try their luck there. They soon discovered that they had no luck at all; Eleanora was again assaulted and soon found herself in all sorts of trouble.

It was the early 1930s: Out of desperation and out of ideas, Eleanora decided to try show business. She auditioned as a dancer for a nightclub and was a rousing failure. Only then did it occur to her to try singing, which met with moderate success. She was able to get by singing for tips in various nightclubs. But then on one particular night, totally broke and facing eviction, Eleanora sang her heart out to the tune “Travelin’ All Alone,” moving everyone to tears. It was then that people discovered that she really could sing, and it didn’t take long for her to be discovered by talent scout and record producer John Hammond.

“Eleanora Fagan” wasn’t a catchy enough name, so Eleanora chose to call herself “Billie” after Billie Dove, one of her favorite actresses, and then adopted her dad’s last name.

Billie Holiday’s recording debut was in 1933 with clarinetist Benny Goodman’s band, followed by a collaboration with pianist Teddy Wilson. “What a Little Moonlight Can Do” and “Miss Brown to You” were two of her early hits. Soon she was recording under her own name and was singing and swinging with the best bands around, including Count Basie, Artie Shaw, and Duke Ellington. The early days weren’t always rosy: while performing in Detroit, Billie had to appear in blackface because some felt she wasn’t quite dark enough.

Dubbed “Lady Day” by saxophonist Lester Young (who she in turn nicknamed “Prez,” short for President), Billie Holiday quickly became one of the most popular jazz vocalists of all time. She had a plaintiff sound, a longing that made you listen to the words. She played with the melodies, sometimes reducing songs to three or four notes like a blues guitarist taking a solo. Her emotions were close to the surface—often she took the audience through the wringer right with her.

Two songs that are even now associated with Billie Holiday are “Strange Fruit” and “God Bless the Child.”

A Jewish schoolteacher had written a poem about the horrors of lynching; it had been set to music and was sometimes performed at teachers’ union meetings in the Bronx. Billie was introduced to “Strange Fruit” and the words haunted her. She wanted to record it, but Columbia wasn’t willing to take the chance of having her record such a controversial song. They temporarily suspended her contract, which allowed her to record the song on Milt Graber’s Commodore label.

“God Bless the Child” was far less controversial, although the words were critical of people who turn their backs on those in need. Billie only had to examine her own life to write the lyrics.

Trouble continued to trail Billie Holiday around every corner. Drinking and drug problems, relations with the wrong men, arrests, a stint in jail, and the revocation of her NYC cabaret card (which kept her from performing in New York for the last decade of her life), eventually led to a tired soul and failing health.

She lost some of the musicality of her voice but not the tragic, raw emotion that continued to move audiences. Her last public appearance, a benefit concert in New York’s Greenwich Village, was in 1959.She could only make it through two songs. A couple of months later, she was in the hospital for liver and heart disease, and to add insult to injury, was charged with drug possession and handcuffed to her hospital bed. She died at age 44 on July 17, 1959 with 70¢ in the bank.

Today, Billie Holiday is remembered as one of the most sensitive and expressive of vocalists. As noted by one of her fans, no one sang the word “love” like she did—she spent her whole life in search of it and never quite found it.

[Billie Holiday recorded on the Columbia, Commodore, Decca, and Verve labels. In addition to the songs mentioned above, some of her best-known songs are “Fine and Mellow,” “Don’t Explain,” and “Good Mrning, Heartache.”]

Posted in Artist of the Month | No Comments »

Monday, March 7th, 2022

Marian McPartland has made jazz piano duets into something of an art form. Sure, it’s been done before, but not very often. There are the Pete Johnson/Albert Ammons duet sessions that made both boogie pianists stars, but save for the occasional live performance where a couple of luminaries may have sat in together to present a finale to a concert, there aren’t that many examples in the jazz canon.

In the 20 or so years that she’s hosted her program Piano Jazz on National Public Radio, Marian McPartland has done her level best to boost the profile of this neglected jazz instrumental format. “Somehow,” McPartland tells me during a phone interview from San Francisco, where she’s playing with her trio at Yoshi’s, “I’ve always been associated with either two or four pianos. The first gig I ever had years ago was a four-piano act in England, where we performed in vaudeville all over the country.”

McPartland was born in England on March 20, 1918, and was playing piano by ear from the time she was three years old. At the age of seventeen, she was accepted by The Guildhall School of Music. There she studied composition and music theory in addition to her piano playing, obtaining a firm grounding in classical piano technique that shows in her playing to this day. But McPartland wanted to play jazz.

She auditioned for a popular English pianist, Billy Mayerl, and was offered a job. Her parents were not happy with her decision to go on the road, but Marian could not be swayed, and finally, they relented. “I do know a lot of young musicians,” she says, “we talk occasionally and one of their big things seem to be that their parents want them to be in some other business, you know, and mine did too, but I didn’t let that stop me. That’s the main thing is be persistent. If you want to do it you’ve got to really get into it, you can’t just halfway do it and have a day job and play a few gigs here and there, you’ve just got to really get into it.” She auditioned for a popular English pianist, Billy Mayerl, and was offered a job. Her parents were not happy with her decision to go on the road, but Marian could not be swayed, and finally, they relented. “I do know a lot of young musicians,” she says, “we talk occasionally and one of their big things seem to be that their parents want them to be in some other business, you know, and mine did too, but I didn’t let that stop me. That’s the main thing is be persistent. If you want to do it you’ve got to really get into it, you can’t just halfway do it and have a day job and play a few gigs here and there, you’ve just got to really get into it.”

Marian really got into her musical career, even though she wasn’t always playing jazz. Once Mayerl’s four piano act broke up, she continued to work in vaudeville and accompanied singers until World War II, when she joined ENSA, the English equivalent of the USO. By 1944 she had joined up with the USO, traveling to France and Belgium, where she met cornetist Jimmy McPartland, her future husband. She has written that during her tours with McPartland’s group playing for GI s on the front lines she learned a lot of the things she needed to know to be a professional jazz pianist, including how to accompany soloists and a great deal of the standard repertoire.

She and Jimmy were married in Aachen, Germany, on February 4, 1946. Soon thereafter, they came back to the States and lived in Chicago, which McPartland refers to as her second home. Jimmy is, of course, known as one of the originators of the “Chicago jazz” style. The University of Chicago’s Jazz Archive contains a large collection of photographs, correspondence, and recordings made available by the McPartlands that tell the story of an important time and place in the development of jazz. Marian appeared at the University’s Mandel Hall on October 20, 2001, in a tribute concert for Jimmy, who passed away in 1991. The event featured Marian and a group of musicians playing music associated with Jimmy, including some who played with him. “We’ve done this before a few years ago, playing all of Jimmy’s recorded music and generally having a good time recalling jokes and funny things that we said to each other.”

The couple moved to New York in 1949, and there she continued to be exposed to all of the great jazz artists of the day. She played her first trio engagement at a club called The Embers, and in 1952 began what became an eight-year stint at the famed Hickory House. By then the trio included drummer Joe Morello, and bassist Bill Crow, who are widely known for their work with Dave Brubeck and Gerry Mulligan, respectively. The trio was named “Small Group of the Year” in 1955 by Metronome magazine. Marian became an established jazz and club pianist; since the Hickory House was located on 52nd Street musicians were always among those in attendance. These often included the likes of Duke Ellington, Oscar Peterson, Billy Strayhorn, and Benny Goodman, as well as one of McPartland’s influences, Mary Lou Williams. The couple moved to New York in 1949, and there she continued to be exposed to all of the great jazz artists of the day. She played her first trio engagement at a club called The Embers, and in 1952 began what became an eight-year stint at the famed Hickory House. By then the trio included drummer Joe Morello, and bassist Bill Crow, who are widely known for their work with Dave Brubeck and Gerry Mulligan, respectively. The trio was named “Small Group of the Year” in 1955 by Metronome magazine. Marian became an established jazz and club pianist; since the Hickory House was located on 52nd Street musicians were always among those in attendance. These often included the likes of Duke Ellington, Oscar Peterson, Billy Strayhorn, and Benny Goodman, as well as one of McPartland’s influences, Mary Lou Williams.

“Well, I always admired Mary Lou; she’s really one of my role models. I always wanted to be able to swing as hard as she did. That was something she could do no matter what the rhythm section was like, and I loved her creativity, she always wanted to be on the edge. Every time I heard her she would be doing something different harmonically. All her compositions are really interesting things.” McPartland and Williams stand side by side in Art Kane’s famous 1958 Great Day in Harlem photograph. The trio recorded some classic sides for Capitol, which remain mysteriously unavailable at this time, though a Savoy reissue of some live dates entitled On 52nd Street is available on CD.

The group reunited for some weekend gigs at Birdland in the Fall of 1998, and those performances can be heard on the Concord disc Reprise.

Originally published at allaboutjazz.com

Photo credits:

- Home – thetimes.co.uk

- Above #1 – nytimes.com

- Above #2 – chicagotribune.com

- Above #3 – digital.nepr.net

Posted in Artist of the Month | Comments Off on Marian McPartland

Thursday, February 10th, 2022

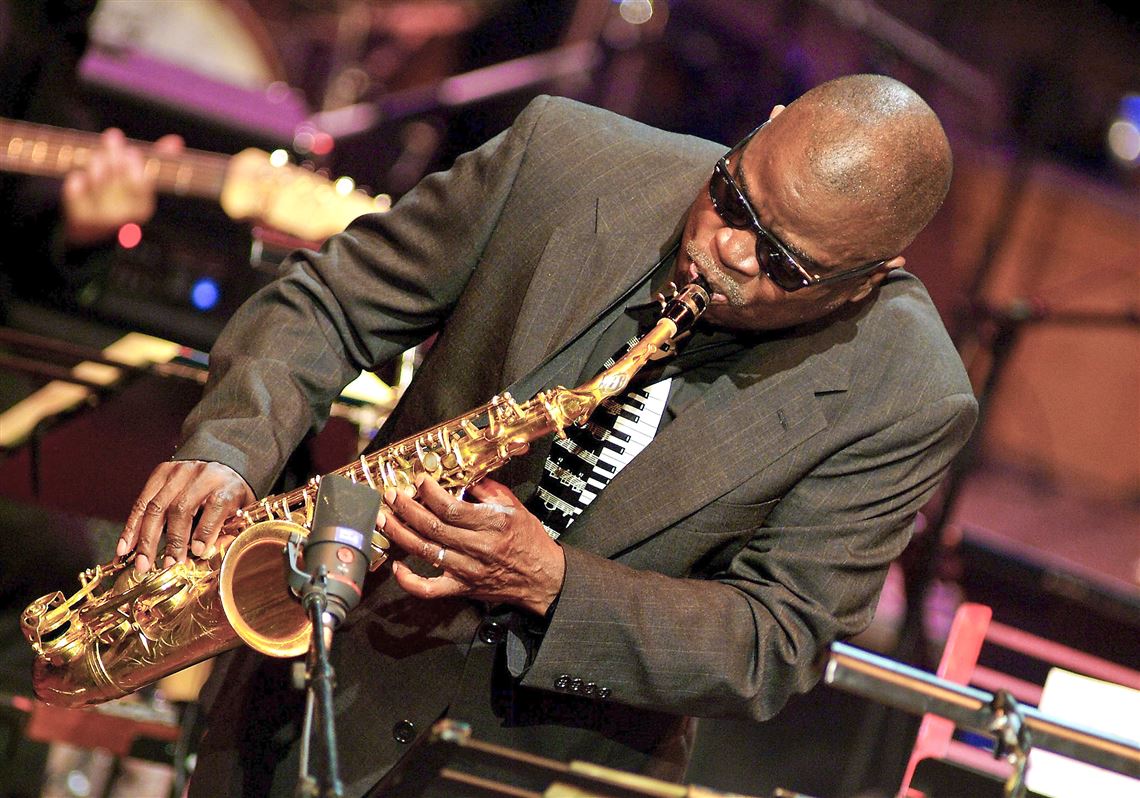

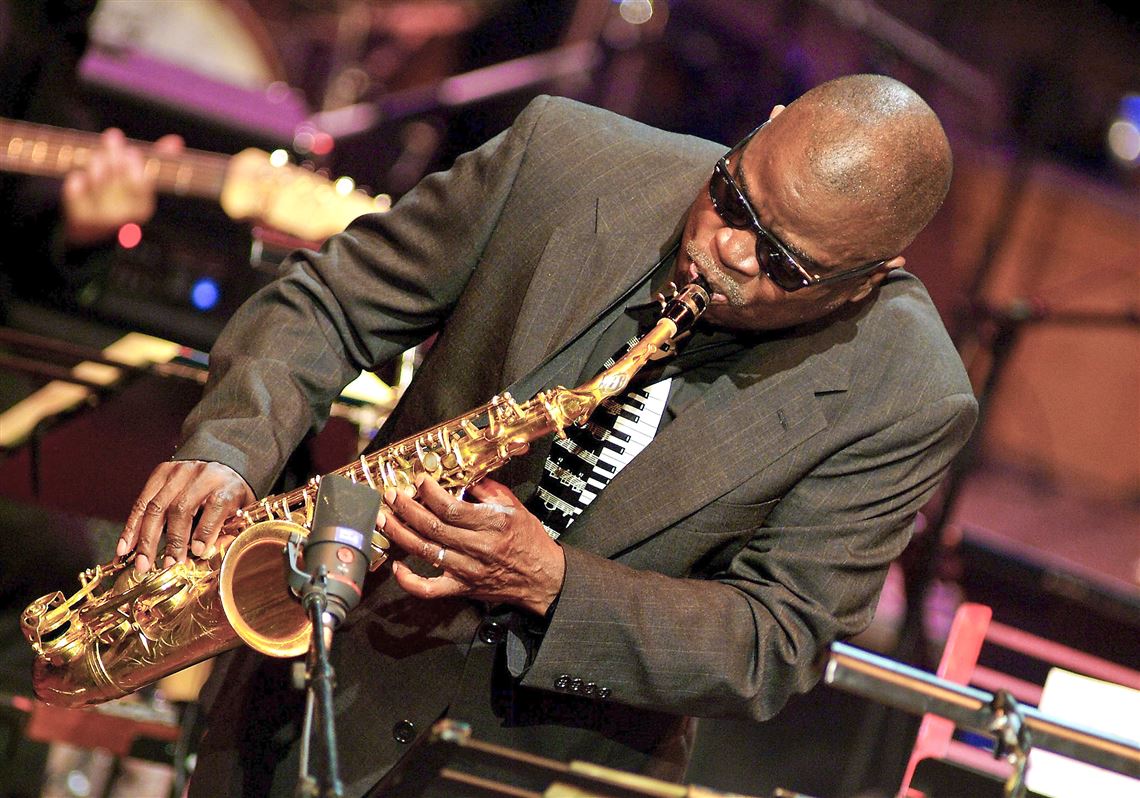

Maceo Parker – saxophone, composer, recording artist, bandleader

His name is synonymous with Funk Music, his pedigree impeccable; his band: the tightest little funk orchestra on earth. Maceo Parker is known by aficionados as a James Brown sideman; appreciated mainly by those in the know. More than a decade and a half later Maceo Parker has been enjoying a blistering solo career. He navigates deftly between ‘60’s scoul and ‘70’s freaky funk while exploring mellower jazz and the grooves of hip-hop.

Maceo Parker was born and raised in Kinston, North Carolina. His uncle, who headed local band the Blue Notes, was Maceo’s first musical mentor. Maceo grew up admiring saxophonists such as David “Fathead” Newman, Hank Crawford, Cannonball Adderley and King Curtis.”I was crazy about Ray Charles, his band, and particularly the horn players”. The three Parker brothers formed the Junior Blue Notes. When Maceo reached the sixth grade, their unle let the Junior Blue Notes perform in between sets at his nightclub engagements. It was his first experience of the stage that perhaps goes some way to explaining a love affair with performing that has increased rather than diminished with time.

In 1964, Maceo and his brother Melvin were in college in North Carolina studying music when a life-changing event took place. James Brown, happened on to an after hours club in which Melvin was drumming a gig. Brown hired the Parker brothers about a year later, and Maceo recollects that he and his brother thought they’d play with JB for about six months and then head back to school. Maceo laughs, “We stayed a lot longer than that.” To most musicologists it’s that fertile group of men who are recognized as the early pioneers of the modern funk. Maceo grew to become the lynch-pin of the James Brown enclave for the best part of two decades, his signature style helped define James’ brand of funk, and the phrase: “Maceo, I want you to Blow,” passed into the language. He’s one of the most sampled musicians around because of the unique quality of his sound.

Originally published at allaboutjazz.com

Photo credits:

- Home – celebvogue.com

- Above #1 – thewickedsound.com

- Above #2 – post-gazette.com

Posted in Artist of the Month | Comments Off on Maceo Parker

Tuesday, January 25th, 2022

Showtime: Sundays at 6:30 p.m. Showtime: Sundays at 6:30 p.m.

“The Measure of Everyday Life” is a weekly interview program hosted by Dr. Brian Southwell featuring social science researchers who endeavor to improve the human condition. It airs each Sunday night from 6:30 – 7 p.m. in the Durham listening area and a podcast of each show is available online the Wednesday following the original airing. The show is made possible by RTI International. Follow @MeasureRadio on Twitter for details and updates.

Posted in Program of the Week | Comments Off on Program of the Week, Jan. 25: The Measure of Everyday Life

Saturday, January 1st, 2022

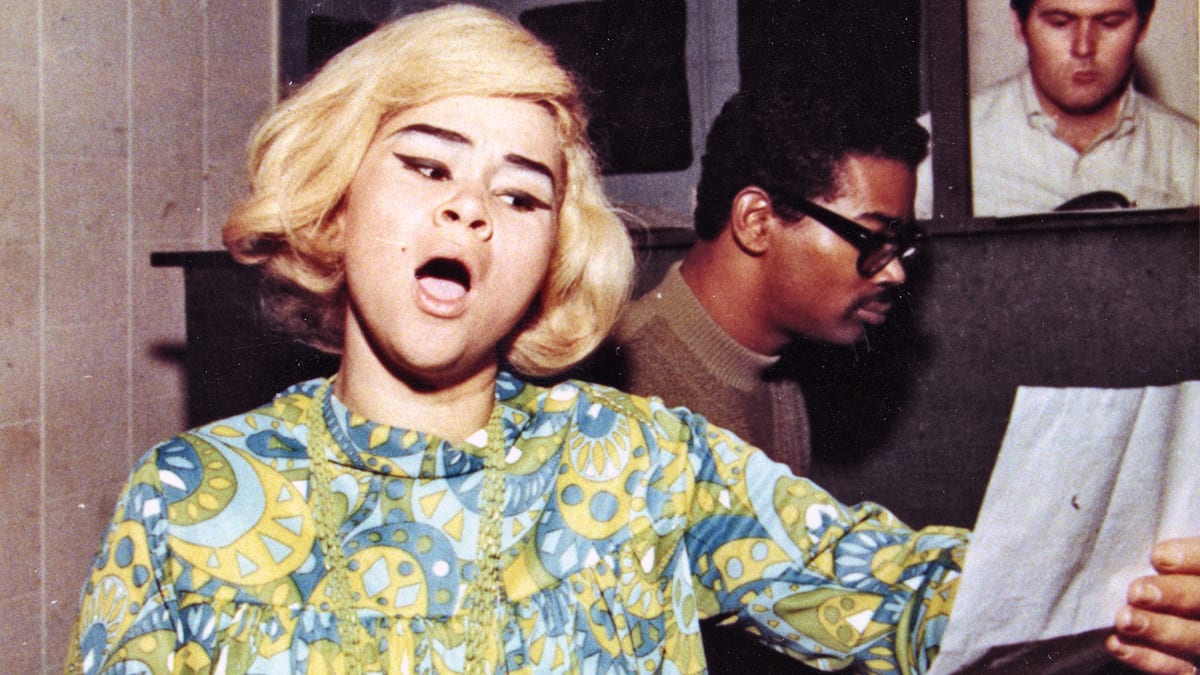

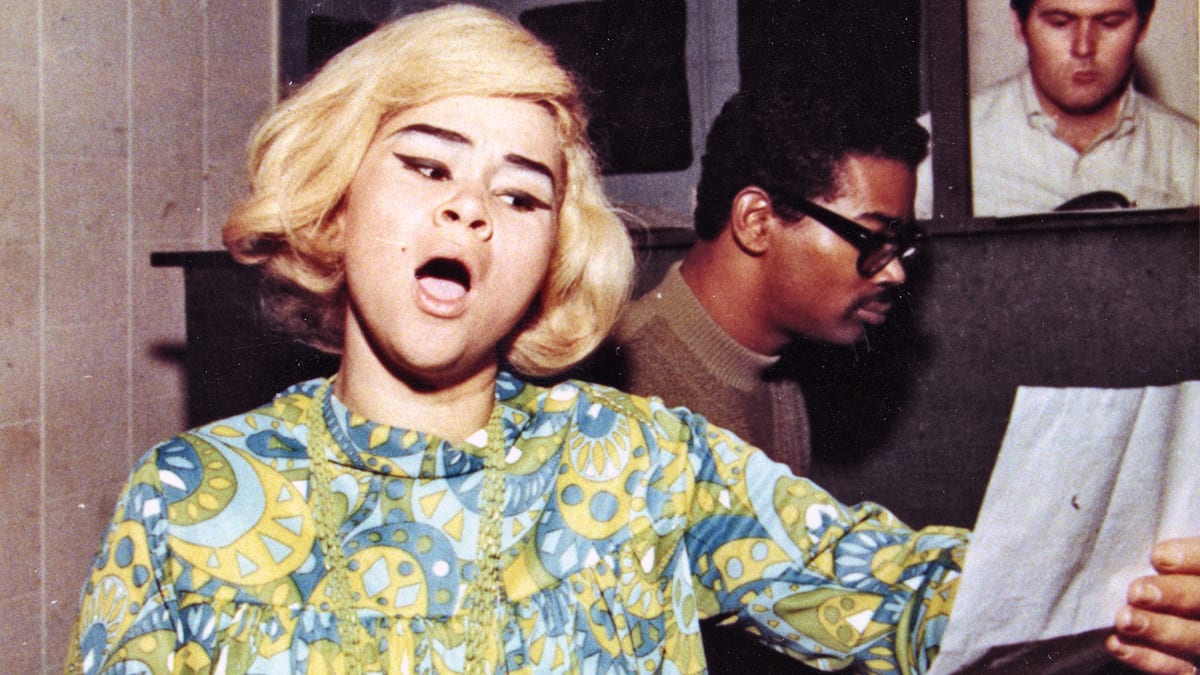

Few female R&B stars enjoyed the kind of consistent acclaim Etta James received throughout a career that spanned six decades; the celebrated producer Jerry Wexler once called her “the greatest of all modern blues singers,” and she recorded a number of enduring hits, including “At Last,” “Tell Mama,” “I’d Rather Go Blind,” and “All I Could Do Was Cry.” At the same time, despite possessing one of the most powerful voices in music, James only belatedly gained the attention of the mainstream audience, appearing rarely on the pop charts despite scoring 30 R&B hits, and she lived a rough-and-tumble life that could have inspired a dozen soap operas, battling drug addiction and bad relationships while outrunning a variety of health and legal problems. Few female R&B stars enjoyed the kind of consistent acclaim Etta James received throughout a career that spanned six decades; the celebrated producer Jerry Wexler once called her “the greatest of all modern blues singers,” and she recorded a number of enduring hits, including “At Last,” “Tell Mama,” “I’d Rather Go Blind,” and “All I Could Do Was Cry.” At the same time, despite possessing one of the most powerful voices in music, James only belatedly gained the attention of the mainstream audience, appearing rarely on the pop charts despite scoring 30 R&B hits, and she lived a rough-and-tumble life that could have inspired a dozen soap operas, battling drug addiction and bad relationships while outrunning a variety of health and legal problems.

Etta James was born Jamesetta Hawkins in Los Angeles, California on January 25, 1938; her mother was just 14 years old at the time, and she never knew her father, though she would later say she had reason to believe he was the well-known pool hustler Minnesota Fats. James was raised by friends and relatives instead of her mother through most of her childhood, and it was while she was living with her grandparents that she began regularly attending a Baptist church. James’ voice made her a natural for the choir, and despite her young age she became a soloist with the group, and appeared with them on local radio broadcasts. At the age of 12, after the death of her foster mother, James found herself living with her mother in San Francisco, and with little adult supervision, she began to slide into juvenile delinquency. But James’ love of music was also growing stronger, and with a pair of friends she formed a singing group called the Creolettes. The girls attracted the attention of famed bandleader Johnny Otis, and when he heard their song “Roll with Me Henry” — a racy answer song to Hank Ballard’s infamous “Work with Me Annie” — he arranged for them to sign with Modern Records, and the Creolettes cut the tune under the name the Peaches (the new handle coming from Etta’s longtime nickname). “Roll with Me Henry,” renamed “The Wallflower,” became a hit in 1955, though Georgia Gibbs would score a bigger success with her cover version, much to Etta’s dismay. After charting with a second R&B hit, “Good Rockin’ Daddy,” the Peaches broke up and James stepped out on her own.

James’ solo career was a slow starter, and she spent several years cutting low-selling singles for Modern and touring small clubs until 1960, when Leonard Chess signed her to a new record deal. James would record for Chess Records and its subsidiary labels Argo and Checker into the late ’70s and, working with producers Ralph Bass and Harvey Fuqua, she embraced a style that fused the passion of R&B with the polish of jazz, and scored a number of hits for the label, including “All I Could Do Was Cry,” “My Dearest Darling,” and “Trust in Me.” While James was enjoying a career resurgence, her personal life was not faring as well; she began experimenting with drugs as a teenager, and by the time she was 21 she was a heroin addict, and as the ’60s wore on she found it increasingly difficult to balance her habit with her career, especially as she clashed with her producers at Chess, fought to be paid her royalties, and dealt with a number of abusive romantic relationships. James’ career went into a slump in the mid-’60s, but in 1967 she began recording with producer Rick Hall at FAME Studios in Muscle Shoals, Alabama and, adopting a tougher, grittier style, she bounced back onto the R&B charts with the tunes “Tell Mama” and “I’d Rather Go Blind.” James’ solo career was a slow starter, and she spent several years cutting low-selling singles for Modern and touring small clubs until 1960, when Leonard Chess signed her to a new record deal. James would record for Chess Records and its subsidiary labels Argo and Checker into the late ’70s and, working with producers Ralph Bass and Harvey Fuqua, she embraced a style that fused the passion of R&B with the polish of jazz, and scored a number of hits for the label, including “All I Could Do Was Cry,” “My Dearest Darling,” and “Trust in Me.” While James was enjoying a career resurgence, her personal life was not faring as well; she began experimenting with drugs as a teenager, and by the time she was 21 she was a heroin addict, and as the ’60s wore on she found it increasingly difficult to balance her habit with her career, especially as she clashed with her producers at Chess, fought to be paid her royalties, and dealt with a number of abusive romantic relationships. James’ career went into a slump in the mid-’60s, but in 1967 she began recording with producer Rick Hall at FAME Studios in Muscle Shoals, Alabama and, adopting a tougher, grittier style, she bounced back onto the R&B charts with the tunes “Tell Mama” and “I’d Rather Go Blind.”

In the early ’70s, James had fallen off the charts again, her addiction was raging, and she turned to petty crime to support her habit. She entered rehab on a court order in 1973, the same year she recorded a rock-oriented album, Only a Fool, with producer Gabriel Mekler. Through most of the ’70s, a sober James got by touring small clubs and playing occasional blues festivals, and she recorded for Chess with limited success, despite the high quality of her work. In 1978, longtime fans the Rolling Stones paid homage to James by inviting her to open some shows for them on tour, and she signed with Warner Bros., cutting the album Deep in the Night with producer Jerry Wexler. While the album didn’t sell well, it received enthusiastic reviews and reminded serious blues and R&B fans that James was still a force to be reckoned with. By her own account, James fell back into drug addiction after becoming involved with a man with a habit, and she went back to playing club dates when and where she could until she kicked again thanks to a stay at the Betty Ford Center in 1988. That same year, James signed with Island Records and cut a powerful comeback album, Seven Year Itch, produced by Barry Beckett of the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section. The album sold respectably and James was determined to keep her career on track, playing frequent live shows and recording regularly, issuing Stickin’ to My Guns in 1990 and The Right Time in 1992. In the early ’70s, James had fallen off the charts again, her addiction was raging, and she turned to petty crime to support her habit. She entered rehab on a court order in 1973, the same year she recorded a rock-oriented album, Only a Fool, with producer Gabriel Mekler. Through most of the ’70s, a sober James got by touring small clubs and playing occasional blues festivals, and she recorded for Chess with limited success, despite the high quality of her work. In 1978, longtime fans the Rolling Stones paid homage to James by inviting her to open some shows for them on tour, and she signed with Warner Bros., cutting the album Deep in the Night with producer Jerry Wexler. While the album didn’t sell well, it received enthusiastic reviews and reminded serious blues and R&B fans that James was still a force to be reckoned with. By her own account, James fell back into drug addiction after becoming involved with a man with a habit, and she went back to playing club dates when and where she could until she kicked again thanks to a stay at the Betty Ford Center in 1988. That same year, James signed with Island Records and cut a powerful comeback album, Seven Year Itch, produced by Barry Beckett of the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section. The album sold respectably and James was determined to keep her career on track, playing frequent live shows and recording regularly, issuing Stickin’ to My Guns in 1990 and The Right Time in 1992.

In 1994, a year after she was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, James signed to the Private Music label, and recorded Mystery Lady: Songs of Billie Holiday, a tribute to the great vocalist she had long cited as a key influence; the album earned Etta her first Grammy Award. The relationship with Private Music proved simpatico, and between 1995 and 2003 James cut eight albums for the label, while also maintaining a busy touring schedule. In 2003, James published an autobiography, Rage to Survive: The Etta James Story, and in 2008 she was played onscreen by modern R&B diva Beyoncé Knowles in Cadillac Records, a film loosely based on the history of Chess Records. Knowles recorded a faithful cover of “At Last” for the film’s soundtrack, and later performed the song at Barack Obama’s 2009 inaugural ball; several days later, James made headlines when during a concert she said “I can’t stand Beyoncé, she had no business up there singing my song that I’ve been singing forever.” (Later the same week, James told The New York Times that the statement was meant to be a joke — “I didn’t really mean anything…even as a little child, I’ve always had that comedian kind of attitude” — but she was saddened that she hadn’t been invited to perform the song.) In 1994, a year after she was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, James signed to the Private Music label, and recorded Mystery Lady: Songs of Billie Holiday, a tribute to the great vocalist she had long cited as a key influence; the album earned Etta her first Grammy Award. The relationship with Private Music proved simpatico, and between 1995 and 2003 James cut eight albums for the label, while also maintaining a busy touring schedule. In 2003, James published an autobiography, Rage to Survive: The Etta James Story, and in 2008 she was played onscreen by modern R&B diva Beyoncé Knowles in Cadillac Records, a film loosely based on the history of Chess Records. Knowles recorded a faithful cover of “At Last” for the film’s soundtrack, and later performed the song at Barack Obama’s 2009 inaugural ball; several days later, James made headlines when during a concert she said “I can’t stand Beyoncé, she had no business up there singing my song that I’ve been singing forever.” (Later the same week, James told The New York Times that the statement was meant to be a joke — “I didn’t really mean anything…even as a little child, I’ve always had that comedian kind of attitude” — but she was saddened that she hadn’t been invited to perform the song.)

In 2010, James was hospitalized with MRSA-related infections, and it was revealed that she had received treatment for dependence on painkillers and was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, which her son claimed was the likely cause of her outbursts regarding Knowles. James released The Dreamer, for Verve Forecast in 2011. She claimed it was her final album of new material. Etta James was diagnosed with terminal leukemia later that year, and died on January 20, 2012 in Riverside, California at the age of 73.

Originally posted on allmusic.com

Photo credit:

Posted in Artist of the Month | Comments Off on Etta James

Sunday, December 5th, 2021

Woody Shaw, Jr. was born in Laurinburg, NC on Christmas Eve (December 24th), 1944. His father, Woody Shaw Sr., was a lead singer in the legendary gospel group known as the Diamond Jubilee Singers. Woody’s father also attended Laurinburg Institute, which was the alma mater of trumpet legend Dizzy Gillespie. It was to these strong roots that trumpeter-composer Woody Shaw attributed his deep sense of pride, cultural awareness and spiritual devotion to music.

At the age of six months old, Woody Jr.’s parents moved to Newark, NJ where he spent most of his childhood. Woody attended Cleveland Junior High School and joined the Junior Elks, Junior Mason, and George Washington Carver Drum and Bugle Corps where he picked up the bugle at an early age. At Cleveland Junior High School, he met an accomplished trumpet teacher, Mr. Jerome Ziering, and during this time, at age 11, he began studying classical trumpet while listening to Dizzy Gillespie, Louis Armstrong, Harry James, and later Clifford Brown. Mr. Ziering wanted Woody to attend The Juilliard School of Music to become a classical trumpeter so he trained young Shaw to become a virtuoso on his instrument. Although he never reached Juilliard, Woody attended the famed Arts High in Newark, which was attended by many legendary jazz artists, such as Wayne Shorter, Sarah Vaughan, organist Larry Young, and many others. Woody began working professionally at age 14.

Woody sat in with countless musicians as a teenager, including Kenny Dorham, Hank Mobley, Lou Donaldson and others in Newark. Along with playing in the local youth bands, this gave him a solid basis in the jazz and African American musical tradition.

1960s 1960s

After playing with famed Latin percussionist Willie Bobo in a band with Chick Corea and saxophonist Joe Farrell, Woody joined the band of legendary saxophonist Eric Dolphy in 1963. It was under the tutelage of Dolphy that Woody would be encouraged to pursue his own musical voice. Dolphy’s complex compositions provided Shaw with a new harmonic concept and different way of looking at music which would shape his approach to the trumpet for years to come. In May of 1963, Woody made his first recorded debut on Eric Dolphy’s Iron Man.

In 1964, at age 19, Woody moved to Paris to work with Dolphy’s band, but Dolphy had passed away, so he wound up living there for a year and half while working with people like Bud Powell, Kenny Clarke, Johnny Griffin, Dexter Gordon, Nathan Davis, Donald Byrd, and other expatriates in Europe. While in Paris, Woody received an invitation to return to the U.S. to join the Horace Silver Quintet, and, in 1965, Woody made his first album for Blue Note Records on Horace Silver’s classic – Cape Verdean Blues.

Later that year Woody made what would be his first major recording as a composer and trumpeter on organist Larry Young’s cult classic, Unity, which featured Joe Henderson on tenor sax and Elvin Jones on drums. Woody wrote three of the six tunes on Unity, entitled “Zoltan,” “Beyond All Limits,” and “The Moontrane,” all of which have become standards. The years following would see Woody working as a sideman for Blue Note and touring with such legends as Jackie McLean, Booker Ervin, Hank Mobley, Art Blakey, Max Roach, Andrew Hill, Joe Henderson, Joe Zawinul, Bobby Hutcherson, Herbie Hancock, McCoy Tyner, and many others (see official discography).

1970s

In 1970, Woody made his first album as a leader entitled Blackstone Legacy (Contemporary), which featured Gary Bartz, Bennie Maupin, Ron Carter, and Lenny White. Shortly thereafter, he recorded a second album entitled Song of Songs and around this time moved to San Francisco where he worked closely with Bobby Hutcherson and others, frequenting the famed Keystone Korner club.

In 1974, Woody returned to the East Coast and signed with Muse Records (now High Note) and recorded several albums such as The Moontrane (1974), Love Dance (1975), Little Red’s Fantasy (1976) Live at the Berliner Jazztage (1976), and Iron Men (1977, a tribute to Eric Dolphy and Andrew Hill featuring Arther Blythe, Muhal Richard Abrams and Anthony Braxton). All of Woody Shaw’s Muse recordings were reissued in The Complete Muse Sessions of Woody Shaw in 2013.

In 1976, Woody also made his first major commercial debut for Columbia Records with Dexter Gordon appearing on Dexter’s resurgent album Homecoming (1976), followed by Sophisticated Giant (1977), and Gotham City (1981). In 1977, by way of an endorsement from Miles Davis, and through his association with Dexter Gordon – who Woody had helped reintroduce to the American jazz scene – Woody received his first major record contract and was signed with Columbia Records.

He then went on to record five historic albums of his own: Rosewood (1977), Stepping Stones (1978), Woody III (1979), For Sure (1980) and United (1981). The recent Complete Columbia Albums Collection of Woody Shaw (co-produced and project-directed by his son, Woody Shaw III) showcases all of Woody’s work from this period including additional unissued material. Musicians included on Woody’s Columbia recordings include Victor Lewis, Carter Jefferson, Onaje Allan Gumbs, Clint Houston, Stafford James, Joe Henderson, Rene McLean, Mulgrew Miller, Larry Willis, Steve Turre and others.

1980s 1980s

Throughout the 1980s, Woody toured with various ensembles which included musicians such as Kenny Garrett (Woody appears as a guest on Kenny Garrett’s debut album Introducing Kenny Garrett), Terri Lyne Carrington, David Williams, Ronnie Burrage, Kirk Lightsey, Ray Drummond, and Cedar Walton. He also recorded a series of albums for Blue Note with his close friend and fellow trumpet legend Freddie Hubbard.

During this period, Woody conducted numerous workshops and clinics around the world. Between the years of 1984 and 1986, Woody traveled all over Europe and to the Middle East and South Asia on the United States Information Service tour where he visited such countries as India, Egypt, the Sudan, and Russia.

After several years of mounting health complications, Woody Shaw suffered fatally from kidney failure and passed away on May 10th, 1989 at the young age of 44. Yet despite a fairly short and challenging life fraught with various health problems, the brilliance of his legacy and the beauty of his music continues to inspire people all over the world. Woody Shaw lives on through his many close friends, students, and thousands of musicians and music lovers who discover, listen to, and explore his life’s work everyday. His legacy is preserved and maintained by his son and namesake, Woody Louis Armstrong Shaw III, who controls all creative, legal, archival and administrative aspects of the Shaw Legacy.

Woody Shaw, Jr. is today considered to be the last major innovator in the lineage of 20th-century trumpet that began with Joe “King” Oliver, Jabbo Smith, Louis Armstrong, and which extended on through the likes of Harry James, Bunny Berigan, Cootie Williams, Roy Eldridge, Dizzy Gillespie, Fats Navarro, Miles Davis, Kenny Dorham, Clifford Brown, Lee Morgan, Booker Little, Donald Byrd, and Freddie Hubbard. Inspired heavily by saxophonists John Coltrane and Eric Dolphy and pianist McCoy Tyner, as well as by various world musics and European classical composers, Woody Shaw sought to extend the legacy of jazz by systematically advancing the tonal, harmonic, melodic, rhythmic and improvisational language of modern trumpet playing. Rooted deeply within the spiritual and intellectual dimensions of both African American and European classical forms (what he termed “Afro-European” musics), and invested in exploring an array of world cultures and systems of thought, Woody Shaw pioneered a new approach to structured improvisational composition in which the totality of his influences would gradually find uncompromising expression.

Musicians whose lives and careers have been directly impacted by Woody Shaw’s work (through interaction, exposure, or direct instruction) include such notables as Wallace Roney, Randy Brecker, Tom Harrell, Dave Douglas, and Terence Blanchard, as well as Wynton Marsalis, Chris Botti, and Ingrid Monson, and countless others, the latter three of whom received grants from the National Endowment of the Arts to study with Woody Shaw during the 1980s.

Originally posted on www.woodyshaw.com/bio

Photo credit:

Posted in Artist of the Month | Comments Off on Woody Shaw

|

As well as being an accomplished musician, Metheny has also participated in the academic arena as a music educator. At 18, he was the youngest teacher ever at the University of Miami. At 19, he became the youngest teacher ever at the Berklee College of Music, where he also received an honorary doctorate more than twenty years later (1996). He has also taught music workshops all over the world, from the Dutch Royal Conservatory to the Thelonius Monk Institute of Jazz to clinics in Asia and South America. He has also been a true musical pioneer in the realm of electronic music, and was one of the very first jazz musicians to treat the synthesizer as a serious musical instrument. Years before the invention of MIDI technology, Metheny was using the Synclavier as a composing tool. He has also been instrumental in the development of several new kinds of guitars such as the soprano acoustic guitar, the 42-string Pikasso guitar, Ibanez’s PM-100 jazz guitar, and a variety of other custom instruments. He took the whole instrument development process into a different level with his mechanical, solenoid driven Orchestrion.

As well as being an accomplished musician, Metheny has also participated in the academic arena as a music educator. At 18, he was the youngest teacher ever at the University of Miami. At 19, he became the youngest teacher ever at the Berklee College of Music, where he also received an honorary doctorate more than twenty years later (1996). He has also taught music workshops all over the world, from the Dutch Royal Conservatory to the Thelonius Monk Institute of Jazz to clinics in Asia and South America. He has also been a true musical pioneer in the realm of electronic music, and was one of the very first jazz musicians to treat the synthesizer as a serious musical instrument. Years before the invention of MIDI technology, Metheny was using the Synclavier as a composing tool. He has also been instrumental in the development of several new kinds of guitars such as the soprano acoustic guitar, the 42-string Pikasso guitar, Ibanez’s PM-100 jazz guitar, and a variety of other custom instruments. He took the whole instrument development process into a different level with his mechanical, solenoid driven Orchestrion. It is one thing to attain popularity as a musician, but it is another to receive the kind of acclaim Metheny has garnered from critics and peers. Over the years, Metheny has won countless polls as “Best Jazz Guitarist” and awards, including three gold records for Still Life (Talking), Letter from Home, and Secret Story. He has also won 20 Grammy Awards in 12 different categories including Best Rock Instrumental, Best Contemporary Jazz Recording, Best Jazz Instrumental Solo, Best Instrumental Composition. The Pat Metheny Group won an unprecedented seven consecutive Grammies for seven consecutive albums. Metheny has spent most of his life on tour, averaging between 120-240 shows a year since 1974. At the time of this writing, he continues to be one of the brightest stars of the jazz community, dedicating time to both his own projects and those of emerging artists and established veterans alike, helping them to reach their audience as well as realizing their own artistic visions.

It is one thing to attain popularity as a musician, but it is another to receive the kind of acclaim Metheny has garnered from critics and peers. Over the years, Metheny has won countless polls as “Best Jazz Guitarist” and awards, including three gold records for Still Life (Talking), Letter from Home, and Secret Story. He has also won 20 Grammy Awards in 12 different categories including Best Rock Instrumental, Best Contemporary Jazz Recording, Best Jazz Instrumental Solo, Best Instrumental Composition. The Pat Metheny Group won an unprecedented seven consecutive Grammies for seven consecutive albums. Metheny has spent most of his life on tour, averaging between 120-240 shows a year since 1974. At the time of this writing, he continues to be one of the brightest stars of the jazz community, dedicating time to both his own projects and those of emerging artists and established veterans alike, helping them to reach their audience as well as realizing their own artistic visions.

A cornerstone of the Blue Note label roster prior to his tragic demise, Lee Morgan was one of hard bop’s greatest trumpeters, and indeed one of the finest players of the ’60s. An all-around master of his instrument modeled after Clifford Brown, Morgan boasted an effortless, virtuosic technique and a full, supple, muscular tone that was just as powerful in the high register. His playing was always emotionally charged, regardless of the specific mood: cocky and exuberant on uptempo groovers, blistering on bop-oriented technical showcases, sweet and sensitive on ballads. In his early days as a teen prodigy, Morgan was a busy soloist with a taste for long, graceful lines, and honed his personal style while serving an apprenticeship in both Dizzy Gillespie’s big band and Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers. As his original compositions began to take in elements of blues and R&B, he made greater use of space and developed an infectiously funky rhythmic sense. He also found ways to mimic human vocal inflections by stuttering, slurring his articulations, and employing half-valved sound effects. Morgan led his first Blue Note session in 1956 and he would record his first two classic albums for the label during 1957 and 1958: The Cooker and Candy. He broke through to a wider audience with his classic 1963 album Sidewinder, whose club-friendly title track introduced the soulful, boogaloo jazz sound. Toward the end of his career, Morgan was increasingly moving into modal music and free bop, hinting at the avant-garde but remaining grounded in tradition; a sound showcased on his 1970 concert album Live at the Lighthouse. He had already overcome a severe drug addiction, but sadly, he would not live to continue his musical growth; he was shot to death by his common-law wife in 1972.

A cornerstone of the Blue Note label roster prior to his tragic demise, Lee Morgan was one of hard bop’s greatest trumpeters, and indeed one of the finest players of the ’60s. An all-around master of his instrument modeled after Clifford Brown, Morgan boasted an effortless, virtuosic technique and a full, supple, muscular tone that was just as powerful in the high register. His playing was always emotionally charged, regardless of the specific mood: cocky and exuberant on uptempo groovers, blistering on bop-oriented technical showcases, sweet and sensitive on ballads. In his early days as a teen prodigy, Morgan was a busy soloist with a taste for long, graceful lines, and honed his personal style while serving an apprenticeship in both Dizzy Gillespie’s big band and Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers. As his original compositions began to take in elements of blues and R&B, he made greater use of space and developed an infectiously funky rhythmic sense. He also found ways to mimic human vocal inflections by stuttering, slurring his articulations, and employing half-valved sound effects. Morgan led his first Blue Note session in 1956 and he would record his first two classic albums for the label during 1957 and 1958: The Cooker and Candy. He broke through to a wider audience with his classic 1963 album Sidewinder, whose club-friendly title track introduced the soulful, boogaloo jazz sound. Toward the end of his career, Morgan was increasingly moving into modal music and free bop, hinting at the avant-garde but remaining grounded in tradition; a sound showcased on his 1970 concert album Live at the Lighthouse. He had already overcome a severe drug addiction, but sadly, he would not live to continue his musical growth; he was shot to death by his common-law wife in 1972. Edward Lee Morgan was born in Philadelphia on July 10, 1938. He grew up a jazz lover, and his sister apparently gave him his first trumpet at age 14. He took private lessons, developing rapidly, and continued his studies at Mastbaum High School. By the time he was 15, he was already performing professionally on the weekends, co-leading a group with bassist Spanky DeBrest. Morgan also participated in weekly workshops that gave him the chance to meet the likes of Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, and his idol Clifford Brown. After graduating from high school in 1956, Morgan — along with DeBrest — got the chance to perform with Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers when they swung through Philadelphia. Not long after, Dizzy Gillespie hired Morgan to replace Joe Gordon in his big band, and afforded the talented youngster plenty of opportunities to solo, often spotlighting him on the Gillespie signature piece “A Night in Tunisia.” Clifford Brown’s death in a car crash in June 1956 sparked a search for his heir apparent, and the precocious Morgan seemed a likely candidate to many; accordingly, he soon found himself in great demand as a recording artist. His first session as a leader was cut for Blue Note in November 1956, and over the next few months he recorded for Savoy and Specialty as well, often working closely with Hank Mobley or Benny Golson. Later in 1957, he performed as a sideman on John Coltrane’s classic Blue Train, as well as with Jimmy Smith.