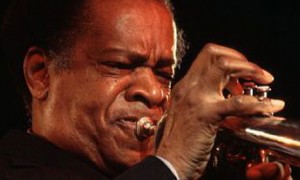

Donald Byrd, legendary Detroit jazz man, dies at 80

Trumpeter, composer and educator Donald Byrd, one of the most important, widely recorded and versatile jazz musicians to come roaring out of Detroit during the city’s golden age of bebop in the 1950s, has died at age 80.

Trumpeter, composer and educator Donald Byrd, one of the most important, widely recorded and versatile jazz musicians to come roaring out of Detroit during the city’s golden age of bebop in the 1950s, has died at age 80.

Byrd’s death, which had been the subject of rumors for several days, was confirmed by his nephew, pianist Alex Bugnon, who posted on Facebook that his uncle died Monday in Delaware, where he lived. Bugnon also wrote that his funeral will be held in Detroit sometime next week.

Byrd’s career traced a remarkable arc, from jazz stalwart in the 1950s and ’60s to best-selling R&B star in the ’70s to the halls of academia as part of the pioneering first wave of African-Americans to teach black music in universities. He earned numerous advanced degrees, mentored several generations of young musicians and became an outspoken authority on African-American history and music.

Born Donaldson Toussaint L’Ouverture Byrd II, on Dec. 9, 1932, he attended Cass Tech, where he studied classical music and was mentored by the legendary band director Harry Begian, a famous disciplinarian. “He’s the one that set the tenor for our lives, for the rest of our lives,” Byrd told the Free Press in 2003.

Byrd played trumpet in military bands during a stint in the Air Force from 1951-53, before graduating from Wayne State University in 1954 with a music degree. Like many of the best young Detroit jazz musicians, he also studied with Detroit’s reigning bebop guru, pianist Barry Harris.

Byrd had a jackrabbit start to his career, landing in New York at age 22 and quickly becoming a ubiquitous presence. He performed and recorded with the cream of the emerging hard bop idiom, including Art Blakey, Max Roach, Sonny Rollins, John Coltrane, Red Garland, George Wallington and countless others.

Byrd’s warmly burnished sound, fluent technique and aggressive-yet-graceful swing was rooted in the style of Clifford Brown, but his gangly, rhythmically loose phrasing was a unique calling card right from the get-go. As Byrd matured in the late ’50s and early ’60s, he tempered his hummingbird flourishes with a cooler sensibility and phrasing that recalled Miles Davis.

Byrd recorded prolifically both as a sideman and a leader, appearing on scores of recordings on the Savoy, Prestige, Riverside and Blue Note labels. He led a feisty quintet with his old pal from Detroit, baritone saxophonist Pepper Adams, from 1958-61. Byrd also gave a young pianist from Chicago named Herbie Hancock his first major exposure by hiring him in 1960.

As a composer, Byrd was proficient in church-inspired shouts, funky and sophisticated blues forms and structurally interesting originals. He had a wider field of vision than many of his peers, exemplified by his influential 1963 LP, “A New Perspective” (Blue Note), which married his small group with a gospel choir.

Byrd never stopped going to school. He earned a master’s degree in music education from the Manhattan School of Music in the late ’50s, studied composition with the famous classical pedagogue Nadia Boulanger in France in the early ’60s, earned a law degree from Howard University in 1976 and a doctorate from Columbia Teachers College in New York in the early ’80s.

Beginning in the ’60s, Byrd taught at many universities, most notably Rutgers, Howard and North Carolina Central.

By the early 1970s, Byrd had begun exploring a danceable fusion of jazz, R&B and soul. In 1973, he teamed with current and former students at Howard, where he was chairman of the black music department, to make the best-selling LP “Black Byrd.” Produced by brothers Larry and Alphonso Mizell, the record and its sequels elevated Byrd into a crossover star.

Byrd’s commercial success made him a controversial figure in the jazz world. Many critics and aficionados considered him a sell-out, but Byrd defended his artistic choices, and saw no reason why he shouldn’t be able to enjoy a good material living as a musician. The funky grooves of Byrd’s fusion albums would later become a favorite source for sampling by hip-hop producers, including the late Detroit artist J Dilla.

In later years, Byrd returned to playing jazz with only mixed success due to a diminished technique. When he last performed in Detroit in 2004 as part of a 70th anniversary celebration at Baker’s Keyboard Lounge, his labored breathing made it difficult for him to play. In 2000, Byrd was named a National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master, the country’s highest honor in jazz.

This article was originally published at Detroit Free Press.