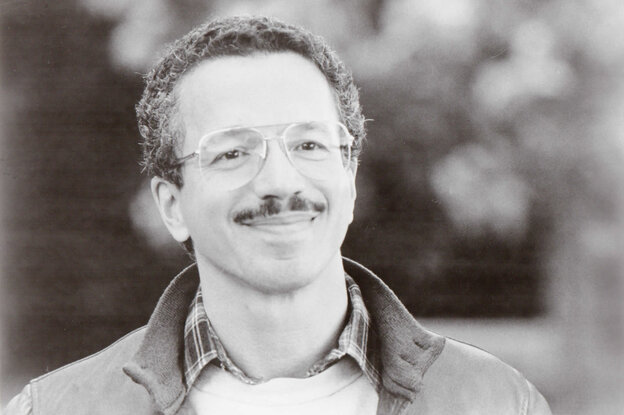

Chico Hamilton, a drummer and bandleader who helped put California on the modern-jazz map in the 1950s and remained active into the 21st century, died on Monday in Manhattan. He was 92.

Chico Hamilton, a drummer and bandleader who helped put California on the modern-jazz map in the 1950s and remained active into the 21st century, died on Monday in Manhattan. He was 92.

His death was announced by April Thibeault, his publicist.

Never among the flashiest or most muscular of jazz drummers, Mr. Hamilton had a subtle and melodic approach that made him ideally suited for the understated style that came to be known as cool jazz, of which his hometown, Los Angeles, was the epicenter.

He was a charter member of the baritone saxophonist Gerry Mulligan’s quartet, which helped lay the groundwork for the cool movement. His own quintet, which he formed shortly after leaving the Mulligan group, came to be regarded as the quintessence of cool. With its quiet intensity, its intricate arrangements and its uniquely pastel instrumentation of flute, guitar, cello, bass and drums — the flutist, Buddy Collette, also played alto saxophone — the Chico Hamilton Quintet became one of the most popular groups in jazz. (The cellist in that group, Fred Katz, died in September.)

The group was a mainstay of the nightclub and jazz festival circuit and even appeared in movies. It was prominently featured in the 1957 film “Sweet Smell of Success,” with Burt Lancaster and Tony Curtis. (One character in that movie, a guitarist played by Martin Milner, was a member of the Hamilton group on screen, miming to the playing of the quintet’s real guitarist, John Pisano.) And it was seen in “Jazz on a Summer’s Day,” Bert Stern’s acclaimed documentary about the 1958 Newport Jazz Festival.

Cool jazz had fallen out of favor by the mid-1960s, but by then Mr. Hamilton had already altered the sound and style of his quintet, replacing the cellist with a trombonist and adopting a bluesier, more aggressive approach.

In 1966, after more personnel changes and more shifts in audience tastes, Mr. Hamilton, no longer on top of the jazz world but increasingly interested in composing — he wrote the music for Roman Polanski’s 1965 film, “Repulsion” — disbanded the quintet and formed a company that provided music for television shows and commercials.

But he continued to perform and record occasionally, and by the mid-1970s he was back on the road as a bandleader full time. He was never again as big a star as he had been in the 1950s, but he remained active, and his music became increasingly difficult to categorize, incorporating elements of free jazz, jazz-rock fusion and other styles.

He was born Foreststorn Hamilton in Los Angeles on Sept. 21, 1921. His father, Jesse, worked at the University Club of Southern California, and his mother, Pearl Lee Gonzales Cooley Hamilton, was a school dietitian.

Asked by Marc Myers of the website JazzWax how he got the name Chico, he said he wasn’t sure but thought he acquired it as a teenager because “I was always a small dude.”

While still in high school he immersed himself in the local jazz scene, and by 1940 he was touring with Lionel Hampton’s big band. After serving in the Army during World War II, he worked briefly with the bands of Jimmy Mundy, Charlie Barnet and Count Basie before becoming the house drummer at the Los Angeles nightclub Billy Berg’s in 1946.

From 1948 to 1955 he toured Europe in the summers as a member of Lena Horne’s backup band, while playing the rest of the year in Los Angeles. His softly propulsive playing was an essential element in the popularity of Mulligan’s 1952 quartet, which also included Chet Baker on trumpet but, unusually, did not have a pianist. The group helped set the template for what came to be known as West Coast jazz, smoother and more cerebral than its East Coast counterpart.

The high profile he achieved with Mulligan emboldened him to try his luck as a bandleader, something fairly unusual for a drummer in the 1950s. His success was almost instantaneous.

He went on to record prolifically for a variety of labels, including Pacific Jazz, Impulse, Columbia and Soul Note. Among the honors he received were a National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters Award in 2004 and a Kennedy Center Living Jazz Legend Award in 2007.

Although slowed by age, Mr. Hamilton continued to perform and record beyond his 90th birthday. He released an album, “Revelation,” in 2011 on the Joyous Shout label, and had recently completed another one, “Inquiring Minds,” scheduled for release in 2014. Until late last year he was appearing at the Manhattan nightclub Drom with Euphoria, the group he had led since 1989.

Mr. Hamilton is survived by a brother, Don; a daughter, Denise Hamilton; a granddaughter; and two great-granddaughters. His brother the actor Bernie Hamilton, and his wife, Helen Hamilton, both died in 2008.

Mr. Hamilton was highly regarded not just for his drumming, but also as a talent scout. Musicians who passed through his group before achieving stardom on their own include the bassist Ron Carter, the saxophonists Eric Dolphy and Charles Lloyd and the guitarists Jim Hall, Gabor Szabo and Larry Coryell. In a 1992 interview with National Public Radio, the saxophonist Eric Person, a longtime sideman, praised Mr. Hamilton for teaching “how to work on the bandstand, how you dress onstage, how you carry yourself in public.”

Mr. Hamilton taught those lessons as a bandleader and, for more than two decades, as a faculty member at the New School for Jazz and Contemporary Music in New York. Teaching young musicians, he told The Providence Journal in Rhode Island in 2006, was “not difficult if they realize how fortunate they are.”

“But,” he added, “if they’re on an ego trip, that’s their problem.”

By Peter Keepnews

Daniel E. Slotnik contributed reporting.

Originally published by www.nytimes.com

By David Brent Johnson

By David Brent Johnson

By Kevin Whitehead

By Kevin Whitehead By Banning Eyre

By Banning Eyre By NPR Staff

By NPR Staff By NPR Staff

By NPR Staff Chico Hamilton, a drummer and bandleader who helped put California on the modern-jazz map in the 1950s and remained active into the 21st century, died on Monday in Manhattan. He was 92.

Chico Hamilton, a drummer and bandleader who helped put California on the modern-jazz map in the 1950s and remained active into the 21st century, died on Monday in Manhattan. He was 92.