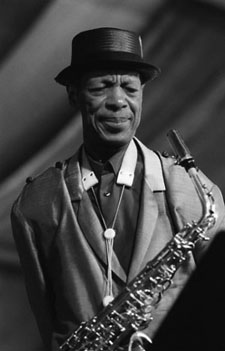

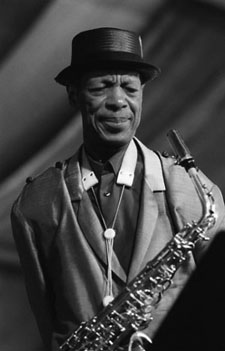

Early on in his career, alto saxophonist Ornette Coleman, recorded an album entitled, The Shape of Jazz To Come. It might have seemed like an expression of youthful arrogance – Coleman was 29 at the time – but actually, the title was prophetic. Coleman is the creator of a concept of music called “harmolodic,” a musical form which is equally applicable as a life philosophy. The richness of harmolodics derives from the unique interaction between the players. Breaking out of the prison bars of rigid meters and conventional harmonic or structural expectations, harmolodic musicians improvise equally together in what Coleman calls compositional improvisation, while always keeping deeply in tune with the flow, direction and needs of their fellow players. In this process, harmony becomes melody becomes harmony. Ornette describes it as “Removing the caste system from sound.” On a broader level, harmolodics equates with the freedom to be as you please, as long as you listen to others and work with them to develop your own individual harmony.

Early on in his career, alto saxophonist Ornette Coleman, recorded an album entitled, The Shape of Jazz To Come. It might have seemed like an expression of youthful arrogance – Coleman was 29 at the time – but actually, the title was prophetic. Coleman is the creator of a concept of music called “harmolodic,” a musical form which is equally applicable as a life philosophy. The richness of harmolodics derives from the unique interaction between the players. Breaking out of the prison bars of rigid meters and conventional harmonic or structural expectations, harmolodic musicians improvise equally together in what Coleman calls compositional improvisation, while always keeping deeply in tune with the flow, direction and needs of their fellow players. In this process, harmony becomes melody becomes harmony. Ornette describes it as “Removing the caste system from sound.” On a broader level, harmolodics equates with the freedom to be as you please, as long as you listen to others and work with them to develop your own individual harmony.

For his essential vision and innovation, Coleman has been rewarded by many accolades, including the MacArthur “Genius” Award, and an induction into the American Academy of Arts and Letter. an honorary doctorate degree from the University of Pennsylvania, the American Music Center Letter of Distinction, and the New York State Governor Arts Award.

But the path to his present universal acclaim has not always been smooth.

Born in a largely segregated Fort Worth, Texas on March 9, 1930, Coleman’s father died when he was seven. His seamstress mother worked hard to buy Coleman his first saxophone when he was 14 years old. Teaching himself sight-reading from a how-to piano book, Coleman absorbed the instrument and began playing with local rhythm and blues bands.

In his search for a sound that expressed reality as he perceived it,

Coleman knew he was not alone. The competitive cutting sessions that denoted ‘bebop’ were all about self-expression in the highest form. “I could play and sound like Charlie Parker note-for-note, but I was only playing it from method. So I tried to figure out where to go from there,” Coleman said.

Los Angeles proved to be the laboratory for what came to be called free jazz. There began to gather around Ornette a core of players who would figure largely in his life: a lanky teenage trumpeter, Don Cherry and a cherubic double bass player with a pensive, muscular style named Charlie Haden, drummers Ed Blackwell and Billy Higgins also joined the intense exploratory rehearsals in which Coleman was honing his vocabulary on a plastic sax, despite the lack of live gigs.

Los Angeles proved to be the laboratory for what came to be called free jazz. There began to gather around Ornette a core of players who would figure largely in his life: a lanky teenage trumpeter, Don Cherry and a cherubic double bass player with a pensive, muscular style named Charlie Haden, drummers Ed Blackwell and Billy Higgins also joined the intense exploratory rehearsals in which Coleman was honing his vocabulary on a plastic sax, despite the lack of live gigs.

But simply by persisting, Coleman’s creativity attracted champions. Bebop bassist, Red Mitchell (an old associate of Cherry’s) brought the saxophone player’s to Contemporary Records’ Lester Koenig, originally intending to sell him some of his compositions. After realizing the difficulty musicians were having in playing the music Koenig asked Coleman if he could play the tunes himself. The meeting led to the Coleman’s debut 1958 album, Something Else.

The energy and electricity that had been building around Ornette and his players exploded during a now legendary season that Coleman played at the Five Spot jazz club in New York in November, 1959. Intrigued by rumors of the unorthodox young Texan’s approach, buzz preceded the shows and as the initial two weeks extended to a six-week run, the revolutionary Coleman quartet became the must-see event of the season.

And yet, as writer and long-time Coleman associate, Robert Palmer, observes in his notes to the Beauty Is A Rare Thing box set of the Atlantic years (Rhino/Atlantic), “The present day listener will most likely hear these pieces as well conceived and superbly realized works on their own terms and will again wonder what all the controversy could have been about.”

Coleman soon began to study of the trumpet and violin expanding the scope of his always prolific composition to include string quartets, woodwind quintets and symphonic works. Coleman used a Guggenheim Foundation grant to write a symphony, Skies of America.

Coleman went on a journey to Morocco in 1973, to work with the Master Musicians of Jajouka in their mountain villages. Following he also visited villages in Nigeria. Soon upon his return Coleman created with a new sound that was a full frontal harmolodic attack, a double whammy of drums and electric bass, dubbed Prime Time.

Coleman’s 1986 collaboration with jazz-rock guitarist Pat Metheny, Song X led to a tour and a new audience. Ornette moved into the broader public consciousness in the late 80s by performing and recording with the Grateful Dead and their hippy virtuoso guitarist, Jerry Garcia. The affection and respect which Coleman and the late Garcia had for one another was captured in the sessions for 1988’s Virgin Beauty (CBS/Portrait).

Coleman’s 1986 collaboration with jazz-rock guitarist Pat Metheny, Song X led to a tour and a new audience. Ornette moved into the broader public consciousness in the late 80s by performing and recording with the Grateful Dead and their hippy virtuoso guitarist, Jerry Garcia. The affection and respect which Coleman and the late Garcia had for one another was captured in the sessions for 1988’s Virgin Beauty (CBS/Portrait).

The new autonomy heralded a season in which Coleman began to reap consistent accolades for his continued adventures in music. He formed the Harmolodic Label and began an association with Polygram France. Over the course of the decade Harmolodic released a number of works beginning with Tone Dialing, on which a Bach prelude is rendered harmolodically.

One of the ultimate American accolades, the MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant, was awarded to Coleman in 1994. In general, rather than simple concerts, Coleman’s performances had by now become big multimedia events that both reflected and impacted on the host town’s community, lasting for several nights at a significant location.

Lincoln Center provided the backdrop for Civilization 1997. A four-night event at Avery Fisher Hall. It began with two nights of Kurt Masur conducting the New York Philharmonic together with Prime Time. Perhaps the most eagerly awaited aspect of all four nights was the first New York appearance in two decades of the Original Quartet, performing all new material. Hearing the familiar, still stimulating blend of Coleman, Haden and Higgins was an emotional experience for many listeners, who found in the depth of the players’ empathy a yardstick of their own lives and the fulfillment of dreams they had when they first heard the Quartet shatter conceptions of music.

A metaphysician, philosopher and eternal student, Coleman continues to confound categorization. His Harmolodic world continues to expand along with the concepts of an artist beyond boundaries. “Most people think of me only as a saxophonist and as a jazz artist,” he once stated, “but I want to be considered as a composer who could cross over all the borders.”

Bio originally published on allaboutjazz.com.

The Boston music scene has suffered another loss with the passing of the beautifully accomplished guitarist, author, and (at the Berklee College of Music) teacher, Garrison Fewell. He was 61. Last year we talked in his Somerville apartment. We were in his music room, where he sat in front of a wall of LPs. “Vinyl makes friends,” he joked to me. (Over the years we had spent afternoons together hunting for records in Manhattan.) His career was varied and in some ways unexpected. Its beginnings, though, were almost inevitable. When I asked about his musical upbringing, he waved at his record shelf, with its alphabetized recordings from Cannonball Adderley to Attila Zoller. He had listened to the hard bop recordings of his era: the Blue Notes, Riverside, and Prestige recordings. Still, starting at age 11, he was also playing the blues, imitating the sounds of John Hurt, Fred McDowell, and Gary Davis.

The Boston music scene has suffered another loss with the passing of the beautifully accomplished guitarist, author, and (at the Berklee College of Music) teacher, Garrison Fewell. He was 61. Last year we talked in his Somerville apartment. We were in his music room, where he sat in front of a wall of LPs. “Vinyl makes friends,” he joked to me. (Over the years we had spent afternoons together hunting for records in Manhattan.) His career was varied and in some ways unexpected. Its beginnings, though, were almost inevitable. When I asked about his musical upbringing, he waved at his record shelf, with its alphabetized recordings from Cannonball Adderley to Attila Zoller. He had listened to the hard bop recordings of his era: the Blue Notes, Riverside, and Prestige recordings. Still, starting at age 11, he was also playing the blues, imitating the sounds of John Hurt, Fred McDowell, and Gary Davis. Early on in his career, alto saxophonist Ornette Coleman, recorded an album entitled, The Shape of Jazz To Come. It might have seemed like an expression of youthful arrogance – Coleman was 29 at the time – but actually, the title was prophetic. Coleman is the creator of a concept of music called “harmolodic,” a musical form which is equally applicable as a life philosophy. The richness of harmolodics derives from the unique interaction between the players. Breaking out of the prison bars of rigid meters and conventional harmonic or structural expectations, harmolodic musicians improvise equally together in what Coleman calls compositional improvisation, while always keeping deeply in tune with the flow, direction and needs of their fellow players. In this process, harmony becomes melody becomes harmony. Ornette describes it as “Removing the caste system from sound.” On a broader level, harmolodics equates with the freedom to be as you please, as long as you listen to others and work with them to develop your own individual harmony.

Early on in his career, alto saxophonist Ornette Coleman, recorded an album entitled, The Shape of Jazz To Come. It might have seemed like an expression of youthful arrogance – Coleman was 29 at the time – but actually, the title was prophetic. Coleman is the creator of a concept of music called “harmolodic,” a musical form which is equally applicable as a life philosophy. The richness of harmolodics derives from the unique interaction between the players. Breaking out of the prison bars of rigid meters and conventional harmonic or structural expectations, harmolodic musicians improvise equally together in what Coleman calls compositional improvisation, while always keeping deeply in tune with the flow, direction and needs of their fellow players. In this process, harmony becomes melody becomes harmony. Ornette describes it as “Removing the caste system from sound.” On a broader level, harmolodics equates with the freedom to be as you please, as long as you listen to others and work with them to develop your own individual harmony. Los Angeles proved to be the laboratory for what came to be called free jazz. There began to gather around Ornette a core of players who would figure largely in his life: a lanky teenage trumpeter, Don Cherry and a cherubic double bass player with a pensive, muscular style named Charlie Haden, drummers Ed Blackwell and Billy Higgins also joined the intense exploratory rehearsals in which Coleman was honing his vocabulary on a plastic sax, despite the lack of live gigs.

Los Angeles proved to be the laboratory for what came to be called free jazz. There began to gather around Ornette a core of players who would figure largely in his life: a lanky teenage trumpeter, Don Cherry and a cherubic double bass player with a pensive, muscular style named Charlie Haden, drummers Ed Blackwell and Billy Higgins also joined the intense exploratory rehearsals in which Coleman was honing his vocabulary on a plastic sax, despite the lack of live gigs. Coleman’s 1986 collaboration with jazz-rock guitarist Pat Metheny, Song X led to a tour and a new audience. Ornette moved into the broader public consciousness in the late 80s by performing and recording with the Grateful Dead and their hippy virtuoso guitarist, Jerry Garcia. The affection and respect which Coleman and the late Garcia had for one another was captured in the sessions for 1988’s Virgin Beauty (CBS/Portrait).

Coleman’s 1986 collaboration with jazz-rock guitarist Pat Metheny, Song X led to a tour and a new audience. Ornette moved into the broader public consciousness in the late 80s by performing and recording with the Grateful Dead and their hippy virtuoso guitarist, Jerry Garcia. The affection and respect which Coleman and the late Garcia had for one another was captured in the sessions for 1988’s Virgin Beauty (CBS/Portrait).