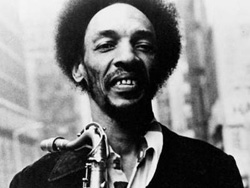

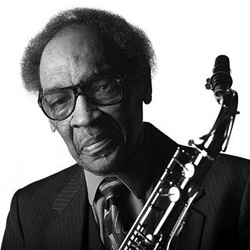

Sam Rivers

Few, if any, free jazz saxophonists have approached music with the same degree of intellectual rigor as Sam Rivers; just as few have managed to maintain a high level of creativity over a long life. Rivers plays with remarkable technical precision and a manifest knowledge of his materials. His sound is hard and extraordinarily well-centered, his articulation sharp, and his command of the tenor saxophone complete. Rivers’ playing sometimes has an unremitting seriousness that can be extremely demanding, even off-putting. Nevertheless, the depth of his artistry is considerable. Rivers is as substantial a player as avant-garde jazz has produced.

Few, if any, free jazz saxophonists have approached music with the same degree of intellectual rigor as Sam Rivers; just as few have managed to maintain a high level of creativity over a long life. Rivers plays with remarkable technical precision and a manifest knowledge of his materials. His sound is hard and extraordinarily well-centered, his articulation sharp, and his command of the tenor saxophone complete. Rivers’ playing sometimes has an unremitting seriousness that can be extremely demanding, even off-putting. Nevertheless, the depth of his artistry is considerable. Rivers is as substantial a player as avant-garde jazz has produced.

Rivers’ father was a church musician, touring with a gospel quartet. Rivers was raised in Chicago and then Little Rock, AR, where his mother taught music and sociology at Shorter College. He began taking piano and violin lessons at about the age of five. He later played trombone, before finally settling on the tenor. Early favorites were Don Byas, Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, and Buddy Tate. Rivers moved to Boston in 1947, where he studied at the Boston Conservatory of Music and, later, Boston University. There, he played in Herb Pomeroy’s little big band, who, in the early ’50s, also featured such players as Jaki Byard, Nat Pierce, Quincy Jones, and Serge Chaloff. Rivers left school in 1952. He moved to Florida for a time, then returned to Boston in 1958, where he again played with Pomeroy. Rivers became active in the local scene.  He formed his own quartet with pianist Hal Galper, and played on his first Blue Note recording session with pianist/composer Tadd Dameron. In 1959, he began playing with 13-year-old Tony Williams. It was about this time that Rivers became involved in the avant-garde. He developed a free improvisation group with Williams. Perhaps befitting his educational background, Rivers approached free jazz from more of a classical perspective, in contrast to the style of his contemporary, Ornette Coleman, who came out of the blues. In the early ’60s, Rivers became involved with Archie Shepp, Bill Dixon, Paul Bley, and Cecil Taylor, all members of the Jazz Composer’s Guild. In 1964, Rivers moved to New York. That July, Miles Davis hired Rivers on Tony Williams’ recommendation. The group played three concerts in Japan; one was recorded and the results released on an LP. In August of 1964, following the brief experience with Davis, Rivers played on Lifetime (Blue Note), Williams’ first album as a leader. Later that year, Rivers led his own session for Blue Note, Fuchsia Swing Song, which documented his inside/outside approach. Rivers led four more dates for Blue Note in the ’60s. In the middle part of the decade, he also recorded with Larry Young, Bobby Hutcherson, and Andrew Hill. In 1969, he toured Europe with Cecil Taylor in a band that also included Andrew Cyrille and Jimmy Lyons. In 1970, Rivers — along with his wife, Bea — opened a studio in Harlem where he held music and dance rehearsals. The space relocated to a warehouse in the Soho section of New York City.

He formed his own quartet with pianist Hal Galper, and played on his first Blue Note recording session with pianist/composer Tadd Dameron. In 1959, he began playing with 13-year-old Tony Williams. It was about this time that Rivers became involved in the avant-garde. He developed a free improvisation group with Williams. Perhaps befitting his educational background, Rivers approached free jazz from more of a classical perspective, in contrast to the style of his contemporary, Ornette Coleman, who came out of the blues. In the early ’60s, Rivers became involved with Archie Shepp, Bill Dixon, Paul Bley, and Cecil Taylor, all members of the Jazz Composer’s Guild. In 1964, Rivers moved to New York. That July, Miles Davis hired Rivers on Tony Williams’ recommendation. The group played three concerts in Japan; one was recorded and the results released on an LP. In August of 1964, following the brief experience with Davis, Rivers played on Lifetime (Blue Note), Williams’ first album as a leader. Later that year, Rivers led his own session for Blue Note, Fuchsia Swing Song, which documented his inside/outside approach. Rivers led four more dates for Blue Note in the ’60s. In the middle part of the decade, he also recorded with Larry Young, Bobby Hutcherson, and Andrew Hill. In 1969, he toured Europe with Cecil Taylor in a band that also included Andrew Cyrille and Jimmy Lyons. In 1970, Rivers — along with his wife, Bea — opened a studio in Harlem where he held music and dance rehearsals. The space relocated to a warehouse in the Soho section of New York City.  Named Studio Rivbea, the space became one of the most well-known venues for the presentation of new jazz. Rivers’ own Rivbea Orchestra rehearsed and performed there, as did his trio and his Winds of Change woodwind ensemble. Rivers’ trio of the time was a free improvisation ensemble in the purest sense. The group used no written music whatsoever, relying instead on a stream-of-consciousness approach that differed structurally from the head-solo-head style that still dominated free jazz. Much of this early- to mid-’70s music was documented on the Impulse! label.

Named Studio Rivbea, the space became one of the most well-known venues for the presentation of new jazz. Rivers’ own Rivbea Orchestra rehearsed and performed there, as did his trio and his Winds of Change woodwind ensemble. Rivers’ trio of the time was a free improvisation ensemble in the purest sense. The group used no written music whatsoever, relying instead on a stream-of-consciousness approach that differed structurally from the head-solo-head style that still dominated free jazz. Much of this early- to mid-’70s music was documented on the Impulse! label.

In 1976, Rivers began an association with bassist Dave Holland. The duo recorded enough music for two albums, both of which were released on the Improvising Artists label. Opportunities to record became more scarce for Rivers in the late ’70s, though he did record occasionally, notably for ECM; his Contrasts album for the label was a highlight of his post-Blue Note work. In the ’80s, Rivers relocated to Orlando, FL, where he created a scene of his own. Rivers formed a new version of his Rivbea Orchestra, using local musicians who made their living playing in the area’s theme parks and myriad tourist attractions. The ’80s and ’90s found Rivers recording albums on his own Rivbea Sound label, as well as a pair of critically acclaimed big band albums for RCA.

By Chris Kelsey-allmusic.com