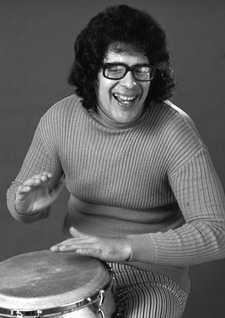

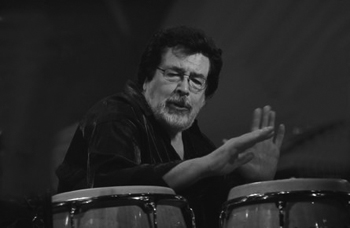

Ray Barretto

For nearly 40 years, conguero and bandleader Ray Barretto has been one of the leading forces in Latin jazz. His hard, compelling playing style has graced the recordings of saxophonists Gene Ammons, Lou Donaldson, and Sonny Stitt, and guitarists Wes Montgomery and Kenny Burrell.

For nearly 40 years, conguero and bandleader Ray Barretto has been one of the leading forces in Latin jazz. His hard, compelling playing style has graced the recordings of saxophonists Gene Ammons, Lou Donaldson, and Sonny Stitt, and guitarists Wes Montgomery and Kenny Burrell.

Born April 29, 1929, in Brooklyn, Barretto is credited for being the first U.S.-born percussionist to integrate the African-based conga drum into jazz. This fact has designated him as on of the early “crossover” artists in jazz — skillfully balancing his Latin leanings and his love for bebop througout a long and successful career.

Barretto’s mother Delores was a financially strapped Puerto Rican immigrant determined to make a better life for her children. While she attended night school to study English, Ray and his siblings were glued to the radio, listening to jazz.

Hearing big band sounds of Duke Ellington, Glen Miller, and Tommy Dorsey, Barretto became enthralled by music. The radio wasn’t the only source of musical entertainment for Barretto — he learned about the majesty of Duke Ellington from a movie called Revelry With Beverly.

Growing up in 1940s America was difficult for the new Puerto Rican immigrants. Barretto and his family were no exception, as they were legally forced to move constantly from one home to another.

To escape the inner-city blues of the Bronx, Barretto enlisted in the army where he was introduced to bebop. After being mesmerized by the 45-rpm of Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie’s “Shaw Nuff,” Barretto discovered one of Gillespie’s most defining songs, “Manteca,” which featured conguero Chano Pozo.

While in the service, Barretto quickly learned that military life was not going to protect him from racial discrimination. When he was stationed in Germany, he found a nightclub that catered only to black GI’s. It was at this club that Barretto began his musical career by playing the back head of a banjo.

While in the service, Barretto quickly learned that military life was not going to protect him from racial discrimination. When he was stationed in Germany, he found a nightclub that catered only to black GI’s. It was at this club that Barretto began his musical career by playing the back head of a banjo.

After his discharge in 1949, Barretto returned to New York City, where he bought a drum set to further pursue his musical interests. The horrifically-named Bucket of Blood club hosted Barretto’s early gigs, but as his technical skills improved he decided to seek out and learn from the bebop masters.

During the early 1950s, mambo was as hot as the bebop movement. Barretto regularly attended concerts at the Palladium Dance Hall, where timbale virtuoso Tito Puente (left) often led his magnificent orchestra. In 1957, Barretto joined the group, replacing the legendary Mongo Santamaria.

Becoming part of Puente’s orchestra, didn’t curb Barretto’s interest in bebop. He was building a solid reputation as a top rate studio percussionist for jazz heroes like drummer Art Blakey, saxophonist Lou Donaldson and guitarist Kenny Burrell.

Unfortunately, at this point in jazz history, the conga drum was viewed as a mere adornment and Barretto rarely performed on the road with these musicians. Donaldson (left), who made some of his most significant Blue Note recordings with Barretto, never took Ray on tour.

Unfortunately, at this point in jazz history, the conga drum was viewed as a mere adornment and Barretto rarely performed on the road with these musicians. Donaldson (left), who made some of his most significant Blue Note recordings with Barretto, never took Ray on tour.

Although many bebop fans despised the conga because of its rigid beats, as time and the music progressed, the instrument became more widely accepted. After several years of being one of the most in-demand sidemen in jazz, Barretto formed his first ensemble, Charanga La Moderna, in 1962.

It was with Charanga that he recorded the boogaloo standard, “El Watusi” in 1962. The song became a huge national hit and helped establish Barretto as a bandleader, but to this day the drummer is somewhat critical of its success.

Also during the early 1960s, Barretto began a his relationship with New York-based record label Fania, which specialized in Latin music and was, according to Barretto, the Latin version of Motown. Over the the next decade, Barretto became a member and eventually music director for the label’s famed Fania All-Stars. The band included trombonist Willie Colon, vocalists Hector Lavoe and Ruben Blades, and pianist Larry Harlow.

Barretto spent nearly three decades with the Fania All-Stars. But as time went on, he found himself frustrated with the limitations of salsa. So in 1992, he formed his current ensemble, New World Spirit, that places a heavier emphasis on bebop jazz. The group released its third album, Portraits in Jazz and Clave, in early 2000. With the success of New World Spirit and his induction into the International Latin Music Hall of Fame in 1999, Ray Barretto is ready help lead Latin jazz into the next millennium.

Bio originally published on NPR’s Jazz Profiles.